by Gregory Kable, PlayMakers Dramaturg

“Lyhte and listin, gentilmen,

That be of frebore blode;

I shall you tel of a gode yeman,

His name was Robyn Hode.”

A Gest of Robyn Hode, (c.1510)

A recent study of the Robin Hood legend cites a survey conducted by London’s Royal Mail on the occasion of the centenary of H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine. British schoolchildren were polled on whether they wished to visit the past or the future and which figures in history they’d most like to meet. Unpredictably, Robin Hood dominated the encounter roster with twenty-two percent of the vote, followed by Elvis Presley at fifteen and Jesus at thirteen percent, respectively.

What accounts for such longevity and mass appeal? If Robin Hood stands for anything, it’s the reminder that we’re all in this together. An injury to one is a wrong done to all. Individuals must take and accept responsibility. That faith in community and shared obligation, along with the purity of vision that compassion and virtue will prevail root this seemingly simple character and narrative in an essential and vital humanity, speaking as urgently to our current moment as it has voiced calls for justice for centuries.

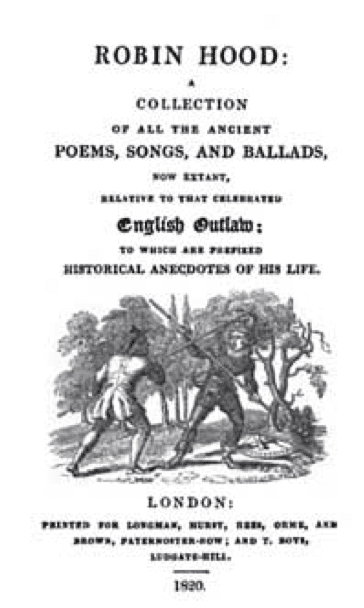

Appropriately for a roving figure, Robin’s appearances in the arts and popular culture are legion. From a mention in the 14th century narrative poem Piers Plowman, through a host of 14th and 15th century Medieval ballads, pastoral May Games festivals and entertainments, to a decisive cameo in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819), scores of literary treatments, multiple operatic versions, especially that of Reginald De Koven, Harry B. Smith, and Clement Scott (1890) featuring the wedding song “Oh Promise Me”, Robin has been a variegated presence. Hollywood epics have starred the likes of Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, Kevin Costner, and Russell Crowe, with yet another version to premiere this November, and the character has morphed through the Rat Pack musical makeover Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), an elegiac Robin Hood with Sean Connery in Robin and Marian (1976), and a gender-bending Princess of Thieves showcasing Keira Knightley (2001).

Appropriately for a roving figure, Robin’s appearances in the arts and popular culture are legion. From a mention in the 14th century narrative poem Piers Plowman, through a host of 14th and 15th century Medieval ballads, pastoral May Games festivals and entertainments, to a decisive cameo in Sir Walter Scott’s Ivanhoe (1819), scores of literary treatments, multiple operatic versions, especially that of Reginald De Koven, Harry B. Smith, and Clement Scott (1890) featuring the wedding song “Oh Promise Me”, Robin has been a variegated presence. Hollywood epics have starred the likes of Douglas Fairbanks, Errol Flynn, Kevin Costner, and Russell Crowe, with yet another version to premiere this November, and the character has morphed through the Rat Pack musical makeover Robin and the 7 Hoods (1964), an elegiac Robin Hood with Sean Connery in Robin and Marian (1976), and a gender-bending Princess of Thieves showcasing Keira Knightley (2001).

Comic Robins have buoyed Mel Brooks’ television satire When Things Were Rotten (1975) and its big screen expansion Robin Hood: Men in Tights (1993), fantasy sightings include Terry Gilliam’s Time Bandits (1981) and Shrek (2001), and the legend enjoys legacies in storybooks, comics, records, costumes, and accessories, British television incarnations from the 1950s, the 1980s, and the 2000s, a Franco-American series in the 1990s, a 1973 Disney animated version, video games, real estate and tax firms, even an investment app. Robin has figured in everything from Warner Brothers cartoons to The Andy Griffith Show, Monty Python and The Muppets to Star Trek: The Next Generation, Dr. Who, and Once Upon a Time, and globetrotted in variants produced in Italy, Germany, the Netherlands, India, Japan, and the Philippines.

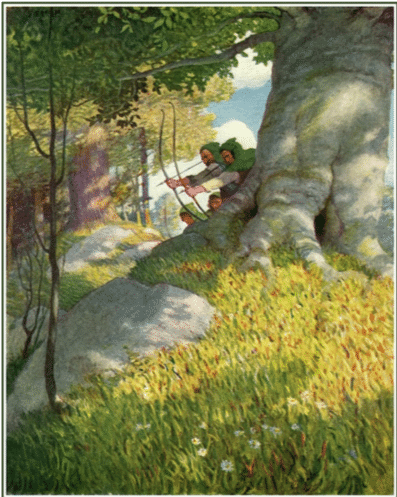

The tales resonate with older stories of mysterious archaic beings, the Wildmen of the Woods, said to inhabit the uncivilized landscapes of European forests, and have informed accounts of real life English outlaws with the obscure but colorful names of Eusatche the Monk, Fouke Fitz Waryn, Gamelyn, the trio of Adam Bell, Clym of the Clough and William of Cloudesley, Scotland’s William “Braveheart” Wallace, and Swiss folk-hero William Tell. All capture something of the Robin Hood mystique, as do American criminal counterparts Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and Bonnie and Clyde. Such overlapping of truth and fiction, furthered by unresolved debates as to whether an historical Robin existed, leads scholars to employ the term “mythstory” to embrace competing perspectives.

The tales resonate with older stories of mysterious archaic beings, the Wildmen of the Woods, said to inhabit the uncivilized landscapes of European forests, and have informed accounts of real life English outlaws with the obscure but colorful names of Eusatche the Monk, Fouke Fitz Waryn, Gamelyn, the trio of Adam Bell, Clym of the Clough and William of Cloudesley, Scotland’s William “Braveheart” Wallace, and Swiss folk-hero William Tell. All capture something of the Robin Hood mystique, as do American criminal counterparts Billy the Kid, Jesse James, and Bonnie and Clyde. Such overlapping of truth and fiction, furthered by unresolved debates as to whether an historical Robin existed, leads scholars to employ the term “mythstory” to embrace competing perspectives.

Further complicating matters, there is no single Robin Hood source to serve as a point of origin. The legend took shape more gradually and in the sphere of folk culture instead of literature, with the earliest ballads, including “A Gest of Robyn Hode”, “Robin Hood and the Monk”, and “Robin Hood and Guy of Gisbourne”, presenting disparate stories while establishing a tradition. English Renaissance Drama made its own contributions to these precedents. Elizabethan dramatist Anthony Munday wrote a pair of tragedies based on Robin in 1597-8 titled The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington and The Death of Robert, Earl of Huntington, and Shakespeare’s As You Like It has strong echoes of the legend proper, while contemporary Ben Jonson left a pastoral piece, The Sad Shepherd; or, A Tale of Robin Hood, unfinished at his death in 1637. In the twentieth century, cinema picked up the thread and continued refining our relationships to the characters and stories. Robin Hood, then, from humble beginnings, evolved into a compelling archetype—pan-epochal, cross-cultural, and multi-generational, he and his colorful cast transcend time, space, and mediums in a way that only a handful of myths have achieved.

Playwright Ken Ludwig has honored and seized on the elastic nature of the Robin Hood legend, employing storytelling, music, dance, direct address, virtuosic doubling of roles, montage, horseplay and swordplay, a tournament, and hair-breadth escapes and rescues as narrative elements, while freely segueing through comedy, adventure, pathos, and romance, for an experience that captures the fullness of his subject. Ludwig also makes valuable additions to the Robin Hood canon. His Robin is dimensional, combining traces of Peter Pan and Batman, as he matures from unruly upstart to cowled crusader. The emphases Ludwig brings to such familiar characters as Maid Marian, Friar Tuck, Little John, Prince John, Sir Guy, and the Sherriff helps us view them anew, and his new figure Doerwynn adds more spark, sass, and depth in her own right.

Playwright Ken Ludwig has honored and seized on the elastic nature of the Robin Hood legend, employing storytelling, music, dance, direct address, virtuosic doubling of roles, montage, horseplay and swordplay, a tournament, and hair-breadth escapes and rescues as narrative elements, while freely segueing through comedy, adventure, pathos, and romance, for an experience that captures the fullness of his subject. Ludwig also makes valuable additions to the Robin Hood canon. His Robin is dimensional, combining traces of Peter Pan and Batman, as he matures from unruly upstart to cowled crusader. The emphases Ludwig brings to such familiar characters as Maid Marian, Friar Tuck, Little John, Prince John, Sir Guy, and the Sherriff helps us view them anew, and his new figure Doerwynn adds more spark, sass, and depth in her own right.

Ludwig’s dramatization highlights that heroes aren’t born, but made; that resistance to oppression is both natural and necessary; that even the most skilled marksmen sometimes err; and most centrally, that justice isn’t blind, it’s intentional. Ludwig’s recognition of the timeliness of this timeless tale is complemented by director Jessie Austrian’s equal mix of humor and heart in the current production. Sherwood, both as play and performance, illustrates critic Northrop Frye’s insight about the ‘Green World’ we enter in pastorals and romances, and their “visualizing the world of desire, not as an escape from ‘reality’, but as the genuine form of the world that human life tries to imitate.”

“Justice, under various names, governs the world … Justice is that which is most primitive in the human soul, most fundamental in society, most sacred among ideas, and what the masses demand today with most ardor.”

Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, c.1840.

Across his career, Ludwig crafts stage experiences that are celebrations of theatre, warranting final connections between the Robin Hood legend and the stage. Theater space, like Sherwood Forest, is a place apart–inside but outside of the everyday realm, a site where the human and the sacred meet, an environment in which alternative worlds thrive. And that familiar designation “Merry Men” was never indicative of gaiety, but derived from Old French meaning brothers in arms. Such welcome bonds born of common purpose are a hallmark of the theatre, as well as an invitation to its audiences. As Robin affirms in the play, “we travel together”, and that’s a contract as true of the stage as in life.

Ludwig’s triumph in Sherwood is to keep the Robin Hood legend both alive and evergreen, conjuring consistency out of composite pieces, fashioning a moving (in the sense of kinetic) and moving (emotionally satisfying) play, and precisely targeting that inspiring core of the Robin Hood story seen whole: a vision, herald, and promise of social parity. That’s an image worth preserving, a cause worth striving for, and, in any age, something to sing about.

Ken Ludwig’s riotous and inspiring Sherwood: The Adventures of Robin Hood opens at at PlayMakers on September 12 and runs through September 30. All youth tickets are just $12, while regular tickets range from $15–57+. For more information and tickets, click here.