by Rachel Pollock, Costume Designer

I’m currently designing costumes for a very exciting project, the professional world premiere of The Parchman Hour, a new play written and directed by Mike Wiley.

The play chronicles the stories and songs of the Freedom Riders, a group composed mostly of college students who, during the summer of 1961, challenged segregation in the southern US by riding Greyhound and Trailways buses into the Deep South and refusing to observe segregated waiting rooms, restrooms, terminal lunch counter seating, and bus seating.

They met with violent resistance–one bus was firebombed and several of the Riders were beaten so badly they had to be hospitalized. They were not deterred, however, and more busloads of them kept coming–eventually over 300 people in all. Ultimately the state of Mississippi began incarcerating them in the notorious Parchman Farm Penitentiary, where they endured cruel abuse but kept their spirits up with songs and a nightly “vaudeville show,” in which they would trade off reciting poetry, delivering speeches and sermons, telling jokes, calling out their contributions to everyone down the row on their cellblock.

In our production, there are several performers (one actor and four musicians) who are costumed as long-term Parchman inmates–men who are not part of the Freedom Riders group, but who instead are part of the Parchman gen-pop, hardened criminals and chain-gang workers who toil in Parchman’s fields day in and day out. The uniforms worn by those prisoner characters are the subject of this post.

In researching what the uniforms looked like, I was specifically looking for photographs of prisoners making music, since the majority of our performers costumed in this way will be prominently featured onstage providing the music for the show.

I initially found some photos of prison bands, inmates who toured providing music for public events. These images weren’t ultimately useful for my research though, beyond novelty. For one thing, all the images i found of prison bands of the era depicted only white prisoners (no surprise, given the segregation and prejudice of the time), and the majority of men serving long sentences in Parchman were black men.

And, our characters haven’t been “polished up for the public.” They aren’t wearing stage-wear uniforms of clean, new fabric. Our guys are inmates playing music for themselves and those with whom they are incarcerated. They need to look like they just came in from the work detail and have sat down to unwind.

These men found time to play music despite incarceration. Our band represents these men.

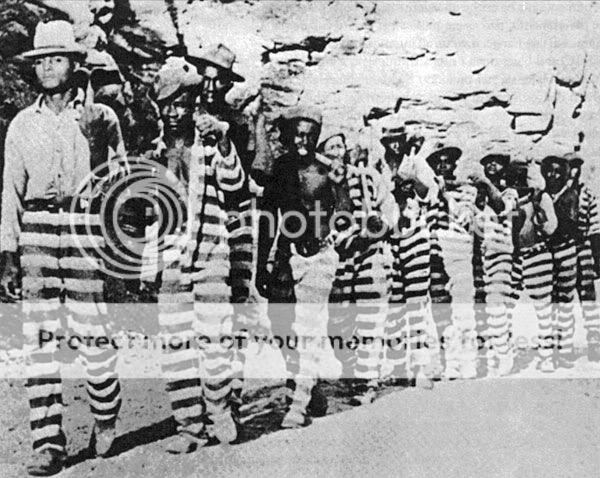

This photo from the early 20th century shows a Parchman work detail returning. Note the variation in sun-fading of the stripes from one man’s trousers to another.

This photo depicts Parchman prisoners in 1948 out on detail as music scholar Alan Lomax records their work songs.

Design collage for Pee Wee and the Band. These images became the basis for our conception of what our inmates’ uniforms would look like.

I looked into what might be available in terms of pre-made prison-striped garments, but options consist of mostly flimsy cartoonish Halloween costumes, or actual modern-day black-and-white striped prison uniforms, which are now mostly made from ultra-durable polyester fabrics. (Not all modern prisoners have the television-cliche orange jumpsuits.) If you’ve ever tried to break down or “fade” polyester, you know what an uphill and ultimately losing battle that would mean for the crafts artisan on this show! And, you can’t put bright white stripes onstage without adversely affecting the lighting, but you also can’t easily tech down a white polyester to a creamier or greyer shade of pale.

I knew that if i wanted to wind up with a group of uniforms that might believably be worn by men serving hard time at Parchman Farm in 1961, we had to explore other options which would afford us more control over our final costumes.

Thankfully, it is entirely feasible in this day and age to simply design your own fabric to whatever specifications you need, and have it digitally printed in your exact yardage requirement. So, this is where the internationally-known, local, print-on-demand fabric production company Spoonflower comes in!

I created a file in Photoshop of a 2″ stripe, already aged and faded to a certain degree, and uploaded it to their site. First, we ordered fat quarters in two of their fabrics–cotton twill and linen/cotton canvas–to test the print, the scale of the stripe, and to compare the hand of the fabric. We also did laundry tests on these sample pieces to see how the hand would change as the costumes were worn and laundered.

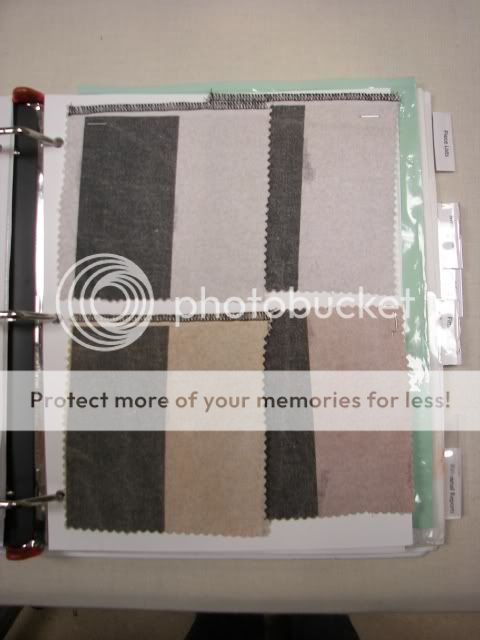

This image shows the cotton twill sample on the left, and the linen/cotton canvas sample on the right. We decided to use the cotton twill, since as the most sturdy weave it would be the most long-wearing for uniforms, and I loved how it reacted to the laundry processing– slight changes in hand and ink retention.

The samples were washed with soda ash on a high-agitation cycle to help break them in, so they wouldn’t look so freshly printed. An unwashed sample is on the right.

We did a set of dye tests at this point, to see what kinds of grime, staining, and yellowing we could incorporate as well. Above are several swatch tests of different washes of dye recipes.

Our shop manager, Adam Dill, contacted the folks at Spoonflower to let them know what we were going to be doing with their fabric and establish a line of communication in case there were any issues or concerns that arose on either end. They were really helpful, and completely on-board about our production timeline and the unusual nature of this project. Then, we ordered 31 yards of the final stripe design in cotton twill.

To give you an idea of the timing and planning of this at this stage of the game, we placed our fabric order two weeks before we wanted to have it in-house. Spoonflower‘s website lists a turnaround time of 6-7 days from order to shipping, with two more days required for larger quantities like our order. We wanted to make sure there was some wiggle-room. This means that as the designer, Mike and i began talking about these costumes and I started my research literally months ago, back in May and June, and the whole process of ordering the samples and doing the laundry tests happened back in August.

We knew, too, that once the fabric arrived, that there needed to be a week built into the schedule for the stuff to get double-processed (laundry loads, then dye washes). So, the planning for using a digital print has to be really on-point with all areas of production and design–you can’t decide to do this on a whim!

Since I am serving as the costume designer on this show, I am not working in my usual capacity as Crafts Artisan. Rather, when i design for the mainstage at PlayMakers, it affords one of our graduate students the opportunity to serve as production crafts artisan on a show. That student handles all the responsibilities which would usually be mine–processing dye requests, aging costumes, rubberizing shoes, making or altering or refurbishing hats, etc. I serve in a mentorship capacity, answering questions about specific processes or pointing them toward particular equipment or media or making sure we have extra hands to get the work done if needed, but the day-to-day running of the crafts sub-departmment during PlayMakers work hours is left to them. They determine their workflow and ask for undergraduate or overhire help as they see fit, and ensure the crafts get done on time and up to par, as i would. I suppose if we did not have a graduate student who expressed interest in crafts, we might overhire a production crafts artisan, but so far it has been something our grads do pursue with enthusiasm.

The first batch, post-dye-treatment! It looks old and dirty and sweaty, and it’s not even a garment yet! Success!

Production Crafts Artisan Adrienne Corral began processing the fabric in batches of six yards each through our 60-gal dye vat. It takes about two hours for her to do one length of the fabric, and is physically demanding work. Imagine suiting up in neoprene scuba gear, rowing a dinghy for fifteen minutes, and then carrying two flour sacks through a sauna. That’s kind of what dyeing cotton twill yardage in a 60-gal vat is like, once you’ve got the neoprene apron and gauntlets and splashproof goggles on, and the bath’s up to a boil!

For reference, here’s another shot with the original freshly-printed unwashed sample swatch on the right, compared to our ready-to-cut pre-faded gross old prison uniform stripe! Great job, Adrienne!

In the next installment, we’ll look at how this fabric yardage turns into costumes, and what else happens to them before they make their appearance onstage in Mike Wiley’s incredible new play!