by Gregory Kable, dramaturg

With 2017 commemorating the 200th anniversary of Jane Austen’s death, what resides in her work to warrant inclusion in ‘a season on the edge’? Certainly the skill and surprises provided by her present adapter, Kate Hamill, whose strengths as a dramatist give this stage translation the vitality, drive, and idiosyncrasy of an original play. But we needn’t probe too deeply in the source material itself to locate in Austen a voice that speaks directly to our cultural moment in addition to expressing key concerns of her age.

Like our present, Austen’s Regency era was a period of transition and sweeping change. The American colonies had won their autonomy (cut comma) and a mentally unstable King George III was threatened with removal. The French Revolution and ensuing Reign of Terror were recent and cautionary histories, while the Napoleonic Wars were further proof of the threats unleashed by a break with tradition. The British Empire was expanding, however unsustainably, in an ongoing bid for supremacy over France.

On other fronts, the accelerating Industrial Revolution was met with violent resistance in Britain’s north, one example of how in culture as a whole, continuity with the past stood in sharp relief against beliefs and behaviors defined as progressive and pushing ahead. A heightened awareness and increased acknowledgment of outmoded structures and hierarchies emboldened challenges to and so a doubling down on rank and privilege. The gap between wealth and poverty widened, while the middle class was being  squeezed, patronized, and ignored.

squeezed, patronized, and ignored.

Women, too, lacked power and influence, and privacy was becoming an outmoded concept, as reputation and rumor joined in a deadly spiral in which opinion and innuendo held increasing sway. In the midst of a façade of business as usual, social upheaval joined economic uncertainty and political unrest in calls for widespread reformist zeal. The sum of these forces was a climate of risk, with its calls for new values and revised views on identity and justice.

In the face of such prevalent insecurity, fastidious adherence to social rituals was one means of warding off the specter of chaos. Austen not only serves as a chief chronicler of a society attempting to reassert control but she also, in an unaffected way, occupies the battlements of major literary questions of her day. “A style of novel has arisen within the last fifteen or twenty years,” noted Sir Walter Scott of Austen’s Emma (1815):

Differing from the former in the points upon which the interest hinges; neither alarming our credulity nor amusing our imagination by wild variety of incident, or by those pictures of romantic affections and sensibility which were formerly as certain attributes of fictitious characters as they are of rare occurrence among those who actually live and die. The substitute for these excitements was the art of copying from nature as she really exists in common walks of life, and presenting to the reader…a correct and striking representation of that which is daily taking place around him.

Scott’s recognition of this prime appeal is itself a rebuttal to the cultural and artistic excesses Austen’s fiction calmly deflates.

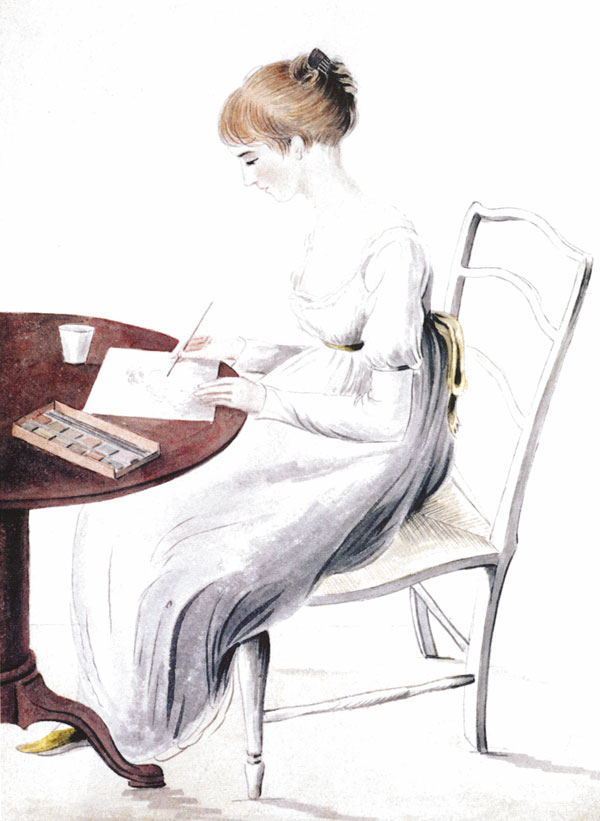

As do many works of the 1790s, Sense and Sensibility takes aim at what it perceives as extravagances of the sensibility movement and its expression in such widely-circulated novels as Clarissa (1748) and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s The Sorrows of Young Werther (1774). Like these predecessors, Austen originally conceived Sense and Sensibility in the form of an epistolary novel (in this case, composed as a series of  letters) entitled Elinor and Marianne around 1795. She moved on from the project to focus on drafts of First Impressions and Susan, which were revised and published as Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey. Published before either in 1811, Sense and Sensibility shares with these concurrent pieces a venturing beyond the familiar terrain of the romance and the gothic, respectively, in order to overturn the assumptions conventional treatments of those genres upheld.

letters) entitled Elinor and Marianne around 1795. She moved on from the project to focus on drafts of First Impressions and Susan, which were revised and published as Pride and Prejudice and Northanger Abbey. Published before either in 1811, Sense and Sensibility shares with these concurrent pieces a venturing beyond the familiar terrain of the romance and the gothic, respectively, in order to overturn the assumptions conventional treatments of those genres upheld.

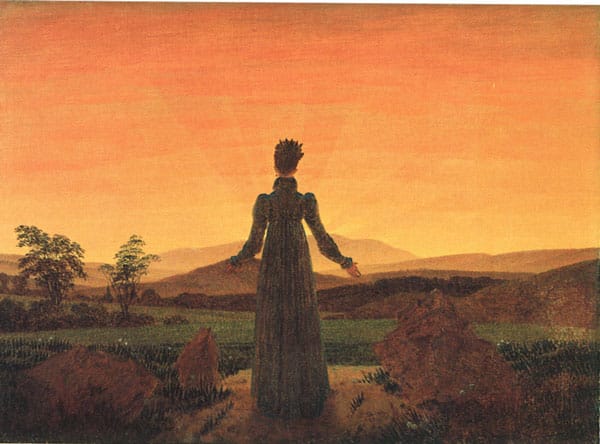

The term “sensibility” emerged from debates surrounding human nature, particularly the relationship between the head and the heart. Enlightenment rationalism advocated for the supremacy of thought over feeling; in contrast, sensibility, as one face of Romanticism, championed emotion as its grounding principle. Poet Hannah More’s “Sensibility” (1782) offers a concise introduction to the latter perspective:

Sweet Sensibility! Thou keen delight!

Thou hasty moral! Sudden sense of right!

Thou untaught goodness! Virtue’s precious seed!

Thou sweet precursor of the generous deed!

Beauty’s quick relish! Reason’s radiant morn,

Which dawns soft light before Reflection’s born.

More’s characterization of feeling as a forerunner to knowledge and moral action lends it a sacred aspect which its advocates promoted and critics disparaged. Austen understood all abstract divisions were necessarily partial. On the one hand, a rationalist’s reserve could read as calculation or stifling repression, on the other, the openness of more emotional natures could be misconstrued as (and even lead to) recklessness and self-indulgence. This latter tumultuous quality finds expression in a period mortuary inscription from Dorchester Abbey:

Reader! If thou hast a Heart famed for Tenderness and Pity, Contemplate this Spot.

In which are deposited the remains of a Young Lady….When Nerves were too delicately spun to bear the rude Shakes and jostlings which we meet with in this transitory world, Nature gave way; She sunk and died a Martyr to Excessive Sensibility.

But the matter passed boundaries of individual temperament. The differing perspectives spoke to competing visions of society itself; in championing nature and instinct the sensibility movement exacerbated conflicts involving class, religion, and culture. Sensibility affirmed a democratic, utopian faith in the equality of emotions as a leveling agent, a thesis its skeptical opponents decried. In an early study of sentimental drama, critic Ernest Bernbaum conceived of these positions in the guise of original figures making their cases in a lucid dispute.

Master Softheart. Wickedness will disappear as the emotions of benevolence and pity are restored to their natural dominance in human character.

Master Hardhead. To soften man’s mind seems to me a dubious way of bettering his heart.

By abandoning that original epistolary structure of Elinor and Marianne, which suggests a surrender to similar norms of clean divisions, Austen decisively mixes these qualities in both of her Sense and Sensibility heroines.

That choice effectively negotiates a peace among those factions of Austen’s age. By refusing schematic clichés, Austen dismisses the naive notion of character as a static vessel of virtue or vice, capturing instead the fact of human ambiguity, resisting hasty judgments, and preventing the objectification of others into easy ideological targets. The Dashwoods and those they encounter in Sense and Sensibility are all buffeted about by the forces of money, property, and status, and even in the context of a narrative pursuing the pleasanter subjects of courtship and marriage, Austen never lets us lose sight of these powerful motives, while respecting us enough to draw our own conclusions about their value as social foundations.

Which brings us back to the present. As scholar Inger Brodey observes, “Austen revises sensibility’s pedagogy to accord with a sense of individual responsibility, an engagement in the community at large, an admiration of tranquility and self-control, and the possibility of community, all of which tend to be absent from its cultish extremes.” The repetition of ‘community’ is significant as a prized quality increasingly absent in our day. Happily, shared features in both Austen and the theatre are this search for a sense of belonging, identification through tolerance and empathy, and a dependable place for reflection and communion. In times where reason feels particularly imperiled, we need the balance that Austen affords.

By temperately appraising the dangers of intellectual detachment, false modesty, and the paralyzing caution of cold logic along with the bombast, irrationality, and narcissism of a culture tyrannized by unruly passions, Austen urges us toward a healthy center, away from the margins and their rhetoric to the world as it is—coaxing us to the edge of civility, of measured discourse and mindful decorum: toward those healing agents on the edge, in a word, of possibility.

Gregory Kable is a resident dramaturg at PlayMakers and lecturer at UNC-Chapel Hill. Sense and Sensibility is on stage from October 18–November 5. Call 919.962.7529 or click here for more information.