Dramaturgy Fellow Series with Lexi Silva.

At the start of Ken Ludwig’s stage adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express by Agatha Christie (Murder), a pensive Hercule Poirot addresses the audience to frame the impending action. “[This case] was certainly the most difficult I ever encountered, and it made me question the very deepest values that I have held since I was a young man.” (Murder). Stuck between a rock and a hard place, Poirot contemplates the tension between moral justice and the law. Though bound to both, Agatha Christie’s most prolific protagonist remains haunted by the case that forged a chasm in his conscience and left him reeling long after the train left the station. Poirot, as both a beloved character and theatrical framing device prompts the audience to consider: what is the cost of justice?

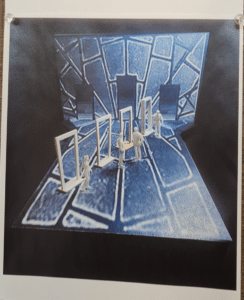

Director Tracy Bersley paints this picture for the audience with the help of Scenic Designer Tony Cisek. Although set pieces and props bring the interior of the train cars to life, the audience sees a more abstract representation of the liminal space of Poirot’s memory. This is not solely an aesthetic choice, but a practical one: the Paul Green Theater’s long thrust stage makes it tricky to put a train onstage.

Poirot draws us into his memory of a murder on the Orient Express, a famous luxury train connecting East and West reserved only for society’s most elite. In Murder, the path taken from Istanbul to Calais follows the Simplon-Orient-Express line, established in 1919. By the 1920s and 30s there was an interconnecting network of Wagons-Lits Company trains with Orient Express as part of their name in addition to the original Orient Express. The Simplon-Orient- Express linked Calais, Paris and Istanbul every day, whereas the Orient Express only carried Paris-Istanbul cars three times a week, although both Orient and Simplon-Orient would have been one combined train east of Belgrade. The train’s journey toward Europe is a homecoming that comes at a higher cost to its passengers than the ticket price.

In Ludwig’s adaptation, the original twelve suspects in Christie’s novel are cut down to eight. The roles consolidated in the stage adaptation are mainly specialized domestic workers. This reflects the social hierarchy present in the primary source, and the smaller cast size makes the work more producible for regional theaters. The correlation between the twelve perpetrators and the twelve members of a jury is easily observed in the novel and still shines through in Ludwig’s abridged cast. In the end, it is still democracy that determines the outcome.

Although it offers levity, glamor and entertainment, Murder on the Orient Express also prompts conversations about democracy, justice and moral responsibility. In the midst of global humanitarian crises and the start of an election year, Poirot’s predicament indicts us, too. I am left wondering if Poirot is not merely concerned with the cost of justice, but with the greater cost of complicity when he addresses the audience for the final time, musing: “But at night, in the darkness, when I am all alone, I ask myself again and again if this was justice; if I did the right thing. And on many such nights, it is not until morning that I can close my eyes.”