By Mark Perry

Wiletta does not come to the Belleville script with any finessed dramaturgical considerations. Her words are more to the point: “It stinks.” That said, her finesse is found in the shield she carries to guard herself from any such psychological and emotional impact. Upon meeting the neophyte John, Wiletta shares the wisdom of her trade, introducing point-by-point a system of working in the white-dominated world of the professional theatre, what we might call code switching and what John dares to call “Tomming.” There is a face and attitude and speech one has towards whites and the white establishment, and there is a face and attitude and speech one has with the black community. There is the Mask, the Front, the Show put on for the Other, and then there is the natural feeling of being with one’s own. In virtually all plays, we gain dramatic irony by seeing more than some of the characters see. Here, Childress provides early-on a concise glossary of African-American code-switching—a code we still recognize, and therefore allows audience members of all colors to participate in the play’s dramatic irony for purposes both comic and serious.

Also originating in the painful crucible of enslavement is another prominent feature of Childress’ world here, and the other side of the Masking described above: the collectivism and group identity of the African-American community. Once in captivity, differing African nationalities quickly merged together into an identity defined by “blackness.” Even in Chaos in Belleville’s newly-formed interracial theatre cast, a black collective is immediately assumed, and no sooner assembled than it is challenged. Jealousy, ambition, narcissism—behaviors frequently reflected in the mainstream American theatre community—do their damage, but the appeal of interracial mingling is also a test. Finally, what happens to a collective when the individual is impelled to arise in an act of conscience that the group would otherwise stifle?

This will be Wiletta’s trial. While she begins the play with no qualms of conscience and no intention of letting down the Mask, her inherent dignity gets the better of her. Her awareness piqued by an acting exercise, she has trouble in mind over a plot that makes no sense and characters whose motivations are irrational. The truth is the writer is unwilling to attribute any agency or any heroic virtue beyond victimhood to African-American characters. She brings this up with Al Manners, the mercurial director who presses the behavioral code of the theatre: Actors do not change the script; they need not worry about the narrative, just to learn it word-perfect and perform it.

To be plain, the subtext not only of Chaos in Belleville but of the rehearsal room is the same exploitative, dehumanizing narrative that serviced the enslavement of the African people in America by the whites: “You don’t have any power. We have the power. Give up, don’t think, don’t question. Or else…” Watching the play from this perspective, one begins to experience synaptic fireworks, marvelous connections this underappreciated playwright made as she realized the dream voiced by Wiletta: “I’ve always wanted to do somethin’ real grand… in the theater.”

The playwright, herself light-skinned and somewhat uneasy about it, stood at an intriguing threshold—one that may have proved too challenging for audiences of its time. This was not a theatre that compromised and showed white projections of blackness, nor was this a theatre “about us, by us, for us…” This was a theatre about encountering “them,” and in several of her most well-known plays, she is relentless about this. These encounters are explosive, and they signal, at best, mindlessness and, at worst, malicious bigotry on the part of the white characters, who stand in positions of relative authority, towards the black female characters, who are distinguished in each case by a deteriorating capacity to hush up, nod and play along. The dynamic of racial interaction she shows is scary and uncertain as to outcome, but the necessity is unrelenting. Pressure is building. What happens to a dialogue deferred?

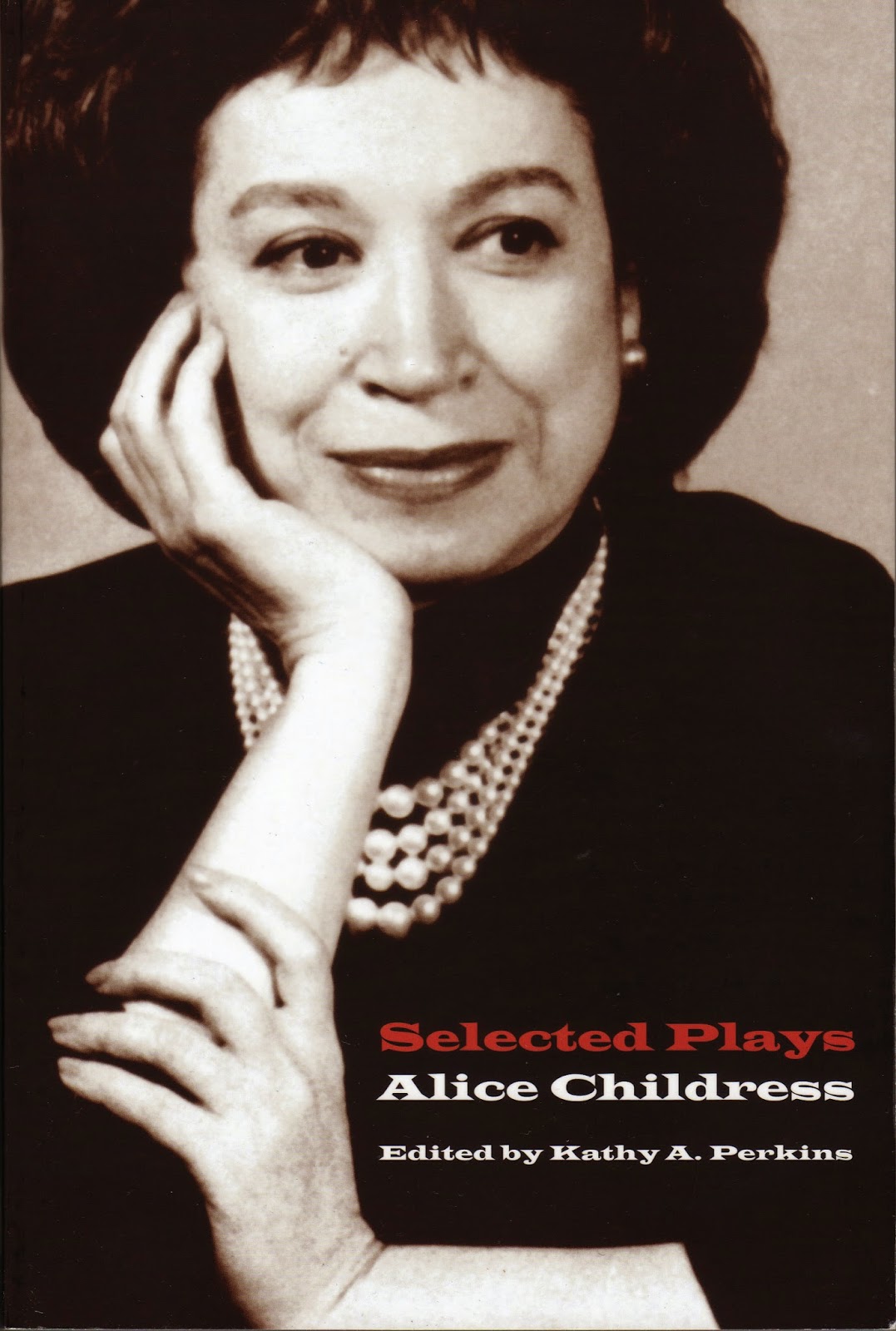

For an excellent resource, see Selected Plays by Alice Childress. (Kathy A. Perkins, editor. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 2011.)

Trouble in Mind is onstage January 21 through February 8. Click here to get your tickets now!