‘Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

—Lord Alfred Tennyson

Throughout the centuries the likenesses of love and war have proved intriguing. In literature, the idea that love and war belong to a distinctive sphere beyond regular rules of fairness is first attributed to poet John Lyly in his novel Euphues: The Anatomy of Wit (1579), which forthrightly states: “The rules of fair play do not apply in love and war.” A quarter century later, Miguel de Cervantes famously compares the laws of love and war in Don Quixote (1604): “Love and War are the same thing, and stratagems and polity are as allowable in the one as in the other.” It was in Francis Edward Smedley’s novel Frank Fairleigh (1850) that the now famous maxim originally appeared: “All is fair in love and war.” Today we are still fascinated by stories about the glories of love and war, particularly when the two are intermingled.

Stephen Massicotte’s Mary’s Wedding takes us on a poetic journey in which we are led through the intimate terrain of haunted memories that traverse majestic prairie fields, setting the scene for romantic love, and the battle-weary fields of the Great War (1914-1918). We follow young Mary Chambers and Charlie Edwards from their first meeting during a thunderstorm on the Saskatchewan prairie to Charlie’s travels across the Atlantic to patriotically join Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) regiment of the Canadian Cavalry Brigade in England, where he experiences trench life in war-ravaged France. The non-linear structure of Mary’s Wedding enables us to theatrically experience simultaneous locations and recurring dreamscapes, which fuse these weighty themes of love and war. The structural and thematic fluidity also imaginatively parallels the fluctuating states of mind of Mary and Charlie as they realize the fragility of love during turbulent times.

|

| Canola Fields south of Leader Saskatchewan |

|

| First World War: French lancers preparing to chase German retreat. Their cavalry lance is the same as that used in the 18th and 19th centuries. WWI marked the end of cavalry combat roles. |

Karen emphasizes the juxtaposition of the prairie field and battlefield images to symbolize love and war.

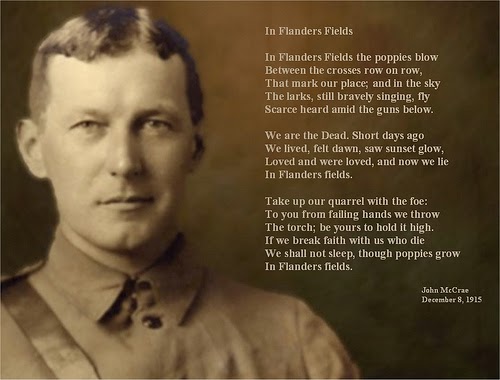

In Mary’s Wedding, Mary and Charlie quote passages from the poetry of Lord Alfred Tennyson (1809-1892), whose Romantic style from the Victorian era inspires them. These allusions add to the poetic features of the play give insight into the characters’ thoughts and feelings. Mary’s allusion to Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” (1833, rev. 1842) mirrors her own views regarding the complications of her war-torn love affair. Charlie alludes to “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (1870), concerning the heroic but futile charge during the Battle of Balaklava (October 1854) in which two thirds of the nearly 670 men were wounded and killed to gain territory in a Russian position during the Crimean War (1853-1856). Charlie’s use of this poem reveals his feelings as he recounts the frightful Battle of Moreuil Wood in which his sergeant successfully leads the patriotic charge brandishing a mere saber against German soldiers armed with rifles and machine guns. Sergeant Flowers is based on Lieutenant Gordon Muriel Flowerdew (1885-1918), who won the Victoria Cross for his valiant advance that led to the German retreat. Flowers’ cavalry charge is the last in recorded military history, and the subsequent apprehension of Moreuil Wood was a milestone in the Great War. To this day, a commemoration is held annually in honor of those who fell during this battle, and plans are in progress for the centenary celebration of Moreuil Wood in 2018. Over 400,000 Canadians served overseas in the Canadian Army during World War I.

No battle is ever won, he said. They are not even fought. The field only reveals to man his own folly and despair, and victory is an illusion of philosophers and fools.

—William Faulkner

Mary’s Wedding is onstage the PRC2 stage April 29-May 3.

Click here for more info or call our box office at 919.962.PLAY (7529).