Richard Wright published Native Son in 1940. The following year Wright and Paul Green, working in Bynum Hall on the UNC-Chapel Hill campus, adapted the novel for the stage. It premiered in New York City at the Mercury Theatre directed by Orson Welles, produced by John Houseman, with Canada Lee as Bigger Thomas. In 1977 the UNC Department of Dramatic Art produced the Green/Wright adaptation to inaugurate the Paul Green Theatre. In 2019 PlayMakers Repertory Company opens its Legacy | NOW season with Nambi E. Kelley’s new adaptation of Native Son.

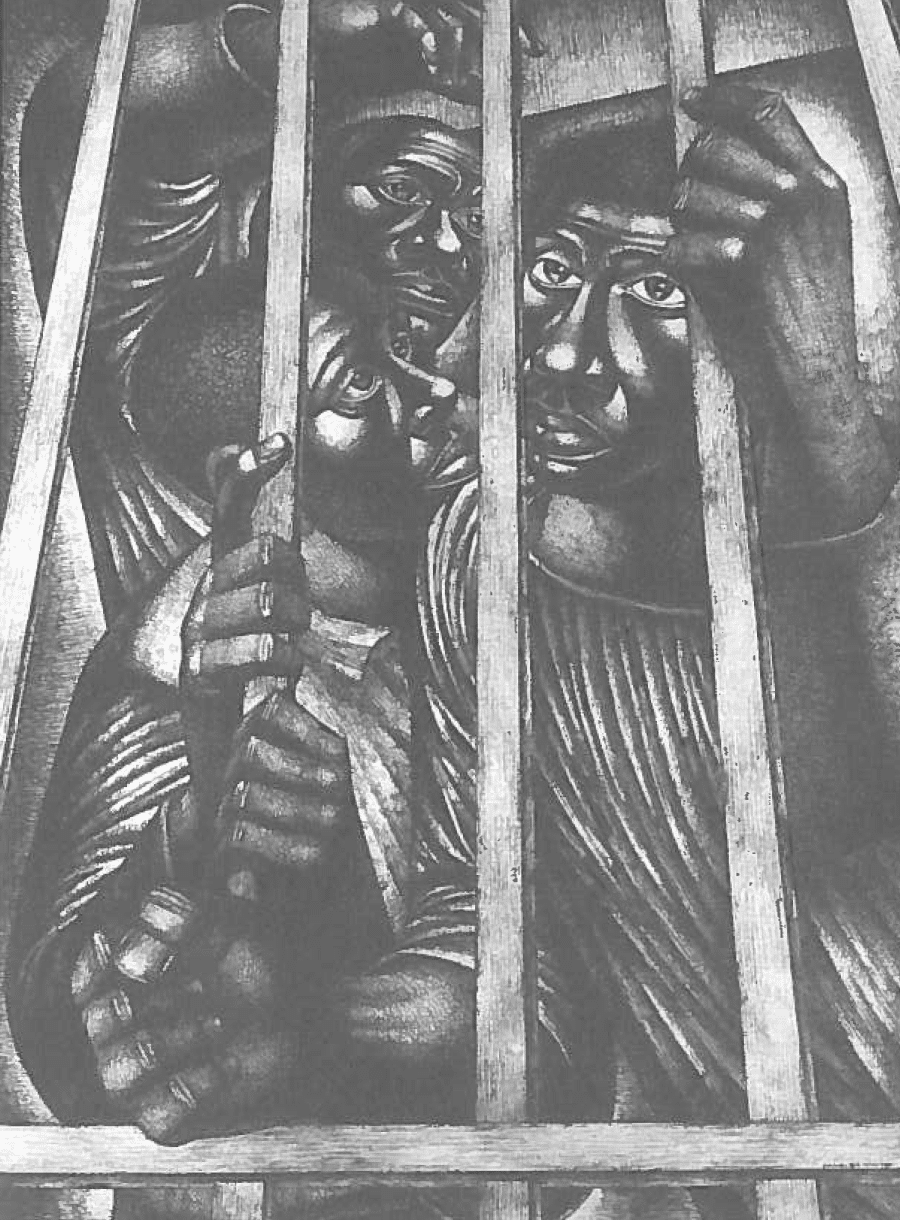

As it charts Bigger Thomas’ journey through both a physical environment and a psychological morass shaped by compression, claustrophobia, and an ever-dwindling range of options, Native Son constantly questions what it means to be a “native” son or daughter of these United States of America? Today we fight battles over the criteria used to grant those fleeing violence and persecution asylum, or to which immigrant populations Emma Lazarus’ words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty apply. Native Son focuses our attention on the poor and the marginalized within our borders. Bigger’s dreams of becoming an airplane pilot are constantly denied due to the color of his skin in a society redolent with oppressive racism. Richard Wright’s novel and Nambi E. Kelley’s play ask us, as does the Black Lives Matter movement, what will be the legacy we leave for future generations now, today? Where do we find hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable barriers?

As it charts Bigger Thomas’ journey through both a physical environment and a psychological morass shaped by compression, claustrophobia, and an ever-dwindling range of options, Native Son constantly questions what it means to be a “native” son or daughter of these United States of America? Today we fight battles over the criteria used to grant those fleeing violence and persecution asylum, or to which immigrant populations Emma Lazarus’ words inscribed on the Statue of Liberty apply. Native Son focuses our attention on the poor and the marginalized within our borders. Bigger’s dreams of becoming an airplane pilot are constantly denied due to the color of his skin in a society redolent with oppressive racism. Richard Wright’s novel and Nambi E. Kelley’s play ask us, as does the Black Lives Matter movement, what will be the legacy we leave for future generations now, today? Where do we find hope in the face of seemingly insurmountable barriers?

Both the play and the novel on which it is based are rooted in the Black Chicago Renaissance from the 1930s until the 1950s. Less well-known than the Harlem Renaissance the Chicago Renaissance, arguably, had more lasting effect. Both Harlem and Chicago were major destinations for southern migrants. Unlike Harlem, Chicago was also an urban industrial center that attracted migrants from across the globe. Where the Harlem Renaissance was primarily aesthetically oriented, the Chicago Renaissance incorporated a working-class and internationalist perspective. As do Wright’s novel and Kelley’s play, Black artists in music, dance, and the visual and literary arts focused on the centrality of race and sex in the distribution of power and the social construction of privilege as they sought to rid “blackness” of its negative connotations.

Chicago was founded by a black man, Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable, who first settled there in 1833. By 1881 Chicago had the second largest population of any city in the U.S. Of its 200,000 inhabitants, 6,480 were African American. At the beginning of the twentieth century the after effects of WWI, the lynching epidemic throughout the south, the increasingly harsh application of Jim Crow laws, later coupled with the Great Depression, fueled what came to be known as the Great Migration of African Americans to the north in general, and to Chicago in particular. Black artists such as Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Mahalia Jackson, Thomas A. Dorsey, Langston Hughes, and Katherine Dunham settled in Chicago. They joined pioneering black journalists like Ida B. Wells, who crusaded against lynching, and Robert Abbot, editor and founder of the Chicago Defender, which became the largest circulation black owned newspaper in the country. The newspaper extended its reach by collaborating with the Brotherhood of Pullman Porters to distribute newspapers throughout the south, frequently in violation of state laws. The importance of newspapers to the dissemination of news in the 1930s is echoed in the play as Bigger consults the morning and evening papers to track the police as they progressively surround him and cut off his escape.

Chicago was founded by a black man, Jean Baptiste Point Du Sable, who first settled there in 1833. By 1881 Chicago had the second largest population of any city in the U.S. Of its 200,000 inhabitants, 6,480 were African American. At the beginning of the twentieth century the after effects of WWI, the lynching epidemic throughout the south, the increasingly harsh application of Jim Crow laws, later coupled with the Great Depression, fueled what came to be known as the Great Migration of African Americans to the north in general, and to Chicago in particular. Black artists such as Richard Wright, Arna Bontemps, Margaret Walker, Mahalia Jackson, Thomas A. Dorsey, Langston Hughes, and Katherine Dunham settled in Chicago. They joined pioneering black journalists like Ida B. Wells, who crusaded against lynching, and Robert Abbot, editor and founder of the Chicago Defender, which became the largest circulation black owned newspaper in the country. The newspaper extended its reach by collaborating with the Brotherhood of Pullman Porters to distribute newspapers throughout the south, frequently in violation of state laws. The importance of newspapers to the dissemination of news in the 1930s is echoed in the play as Bigger consults the morning and evening papers to track the police as they progressively surround him and cut off his escape.

The Black Chicago Renaissance was affected by local, national, and international events from the Scottsboro boys “rape” trial in 1931 to Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in 1935. The period can be bookended by the deaths of two Chicago black males. On July 27, 1919 a teenager named Eugene Williams unwittingly swam across the invisible line that separated black and white beaches on Lake Michigan and was beaten to death. In what came to be known as the “Red Summer of 1919”, his murder touched off the deadliest race war in Chicago history as marauding white gangs stormed into black neighborhoods, forcing black residents to defend themselves. Thirty-eight men and women, both black and white, died and more than five hundred were injured. On August 28, 1955 Emmet Till’s body was pulled out of Mississippi’s Tallahatchie River. Mamie Till-Mobley’s decision to leave her son’s casket open provided some of the most enduring images of the Civil Rights Movement, adding cries against social injustice in multiple forms to those found in Native Son.

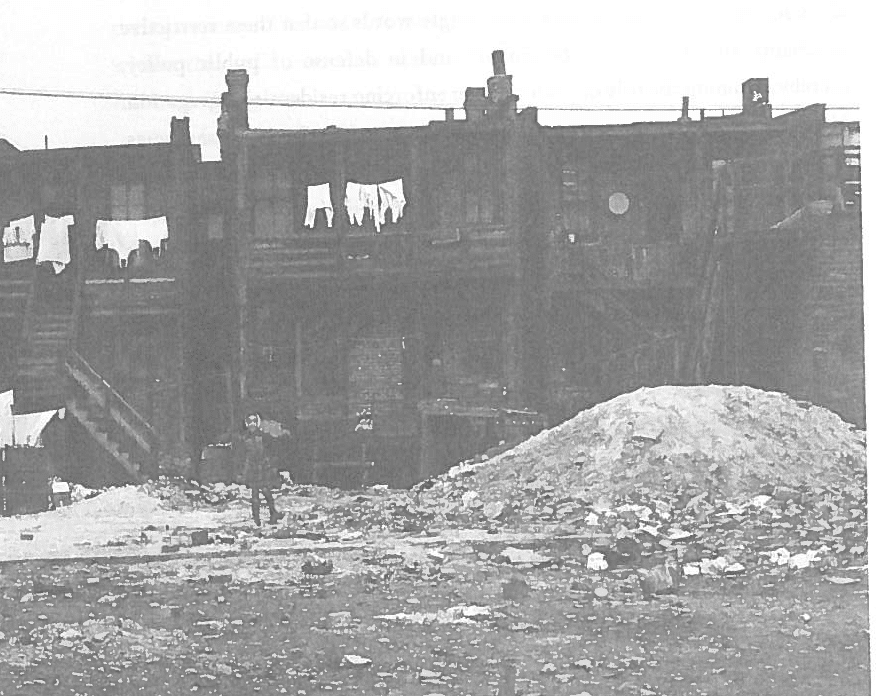

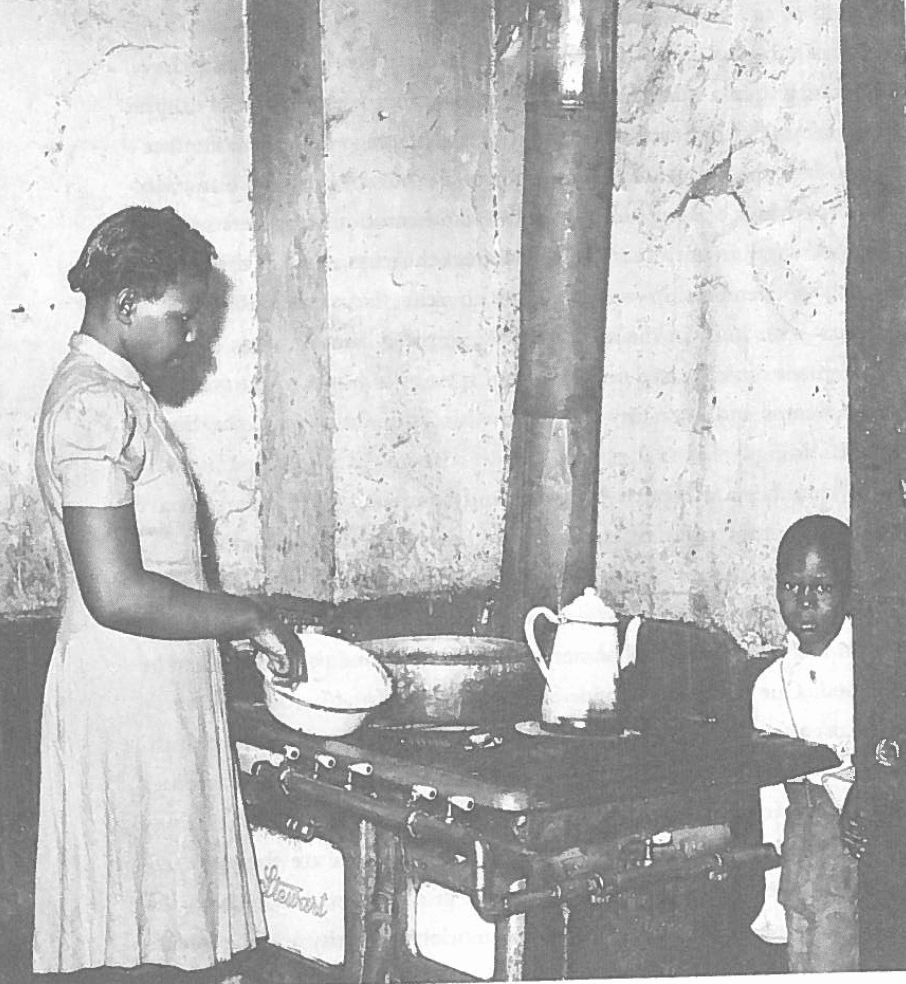

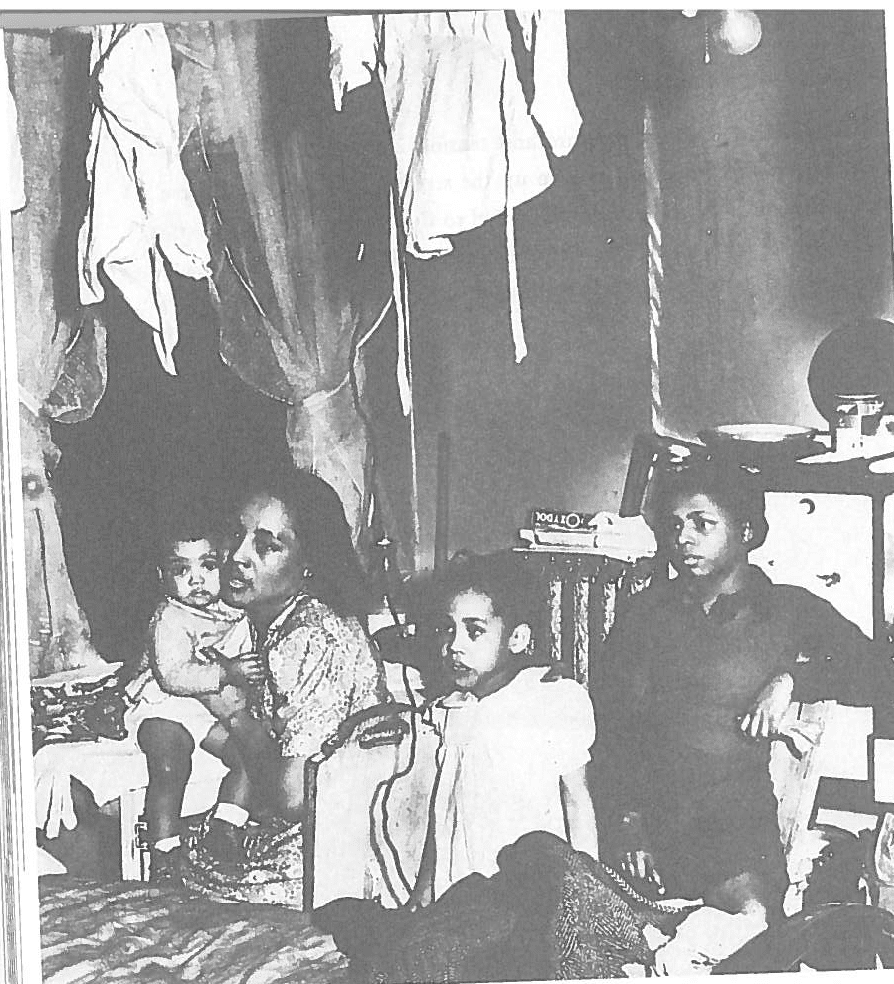

Conscious city planning policy, beginning with the “1912 vice purge” that moved saloons, gambling dens, dance halls, and brothels out of largely white downtown areas and into the Black Belt on the South Side, created a “social myth” that black neighborhoods and vice were naturally linked. All of this meant that black artists were determined to connect fighting against fascism, Nazism, and colonialism abroad to fighting against legal segregation and social injustice at home. Maren Stange’s Bronzeville: Chicago in Pictures and Richard Wright’s 12 Million Voices documented the appalling conditions in the kitchenettes where Bigger Thomas’ family and the vast majority of Chicago’s black citizens were forced to live by white realtors and zoning officials. Charlotte Pierce Baker described these South Side tenements as “vertical slave ships”. Both the play and the novel Native Son demonstrate the direct effects of physical environment on human behavior with Kelley’s adaptation employing theatrical devices such as splitting Bigger’s character in two and fracturing time to emphasize the growing pressures on Bigger’s psyche. Space and place are fundamental to an understanding of Bigger Thomas who, like his fellow black Chicagoans, is denied any control over his space and place.

Conscious city planning policy, beginning with the “1912 vice purge” that moved saloons, gambling dens, dance halls, and brothels out of largely white downtown areas and into the Black Belt on the South Side, created a “social myth” that black neighborhoods and vice were naturally linked. All of this meant that black artists were determined to connect fighting against fascism, Nazism, and colonialism abroad to fighting against legal segregation and social injustice at home. Maren Stange’s Bronzeville: Chicago in Pictures and Richard Wright’s 12 Million Voices documented the appalling conditions in the kitchenettes where Bigger Thomas’ family and the vast majority of Chicago’s black citizens were forced to live by white realtors and zoning officials. Charlotte Pierce Baker described these South Side tenements as “vertical slave ships”. Both the play and the novel Native Son demonstrate the direct effects of physical environment on human behavior with Kelley’s adaptation employing theatrical devices such as splitting Bigger’s character in two and fracturing time to emphasize the growing pressures on Bigger’s psyche. Space and place are fundamental to an understanding of Bigger Thomas who, like his fellow black Chicagoans, is denied any control over his space and place.

The Black Chicago Renaissance was an artistic response to the conditions of black life in the city, both a celebration of blackness and a means of escape from a harsh environment. There is a direct connection between the work of artists in the Chicago Renaissance and the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s when Stokely Carmichael declared “Black is Beautiful” to the Black Arts Movement spawned by playwrights such as Ed Bullins, Adrienne Kennedy, and Amiri Baraka, and to myriad black writers, artists, playwrights, and filmmakers as they explore the spaces and places claimed by bodies of color today. Join director Colette Robert, her design team, and cast as PlayMakers Repertory Company’s production of Native Son thrusts you into Bigger Thomas’ world and, amidst all of its pressures and contradictions, seeks a way for Bigger to fly.