Seeking the Sacred in a Secular South

You got to give yourself a reason to rejoice.

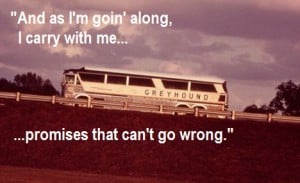

The Road Trip. It’s an American institution, obsession, and rite of passage. Traveling on, hitting the highway, whether following well-worn paths or “lighting out for the territories” in Huck Finn’s famous phrase, the lure of the road occupies a hallowed place in our national consciousness, beckoning in mutual directions from the intersection of leisure and longing. In America, our psyches and physical distance seem as interdependent as strands of DNA.

The Road Trip. It’s an American institution, obsession, and rite of passage. Traveling on, hitting the highway, whether following well-worn paths or “lighting out for the territories” in Huck Finn’s famous phrase, the lure of the road occupies a hallowed place in our national consciousness, beckoning in mutual directions from the intersection of leisure and longing. In America, our psyches and physical distance seem as interdependent as strands of DNA.

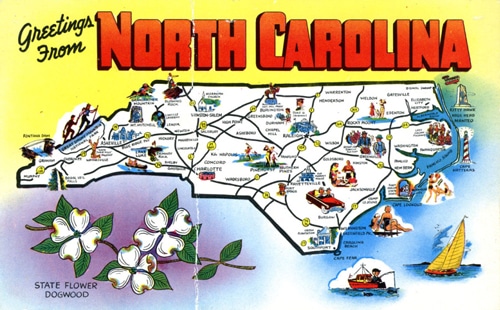

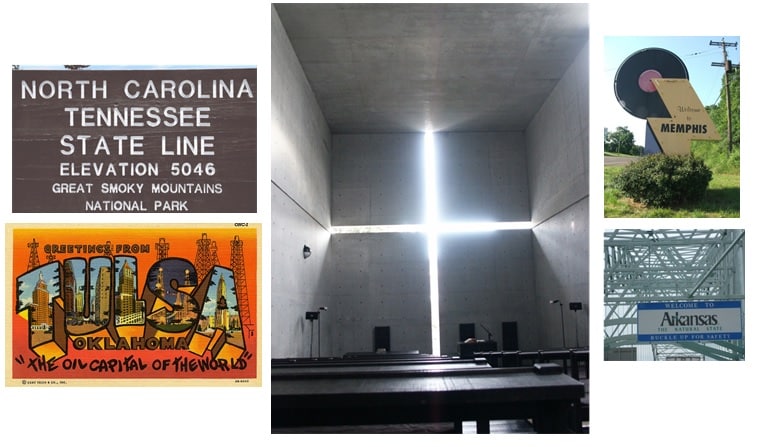

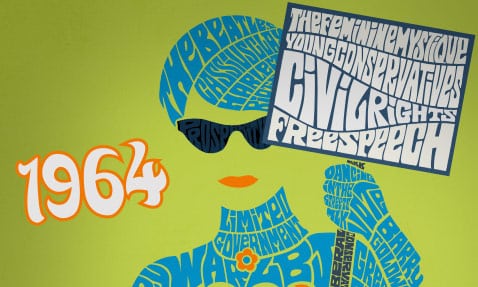

If we’re each, as is said, the sum of our journeys, this passionate and poignant musical by Jeanine Tesori and Brian Crawley benefits from its especially rich itinerary. In the Fall of 1964, the indomitable Violet Karl embarks on a bus pilgrimage from her remote mountain town in western North Carolina to Oklahoma to appeal to a televangelist she believes can remove the facial scar which has disfigured and isolated her since childhood. Among a host of fellow travelers on route she meets two soldiers, one white and one black, destined for their next post in Arkansas and potentially Vietnam. Friendships and tentative romances arise amid the shifting landscapes of the American South and its changing soundtracks of bluegrass, country and western, blues, and gospel music. Violet is ultimately compelled to confront her illusions and unresolved conflicts, as must the nation as a whole in wrestling with the initial volatility of the Civil Rights Movement and an escalating presence in Southeast Asia. The musical’s core themes of perseverance and self-discovery are just as critical in our own historical moment as they are for the fictional Violet herself. With honesty, emotional velocity, and indelible lyricism, Violet explores how we personally and collectively seek to come to terms with and release the past, affirm life and love, and in the process, heal our wounds.

I’m Violet Karl. [From] Spruce Pine.

Violet has deep roots in both North Carolina and our local community. The piece is based on “The Ugliest Pilgrim,” a widely admired and anthologized 1969 story by Doris Betts, a longstanding Distinguished Professor at UNC prior to her death in 2012.

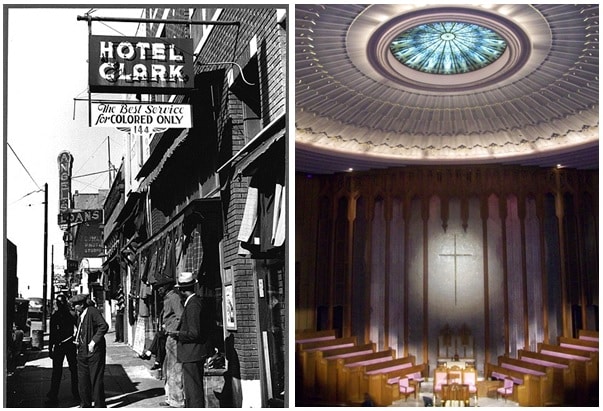

The dynamic between extremes in the sacred and secular inform Violet’s journey.

The dynamic between extremes in the sacred and secular inform Violet’s journey.

The 1997 Off-Broadway musical adaptation enjoyed success, with PlayMakers Repertory Company producing its regional premiere in 1998 before a strikingly overdue debut on Broadway in 2014 featuring a breakout performance by theatre diva Sutton Foster. It was also translated to film in a 1981 short directed by Oscar-winner Shelley Levinson. Thus, in Violet, we have a musical with not only a significant, and positive, female protagonist, but one conceived and realized in its respective mediums by influential women in stubbornly male-dominated professions of Southern Literature, Hollywood cinema, and Broadway Musicals. In a context when gender inequality is such a socially and politically contested issue, it makes perfect sense to extend that debate into the immediate landscape of our campus arts scene.

Doris Betts and the 1969 journal debuting “The Ugliest Pilgrim”.

Violet stands not only as an image of willed motion from place to place, but additionally, as reinforced in its creative interpreters, as a symbol of possibility or the journey from self to self. This aspect finds resonance in a meditation on America’s interstate roadways entitled Highway: America’s Endless Dream (1998), in which essayist Phil Patton observes:

In America, the driver between political states is also the driver between states of mind. This who drive are often alone, often between lives. They are abandoning old identities and looking for new ones, but are most themselves in the interval. Some drive to remember, others to forget.

As a character, Violet affords a profoundly empathetic figure and her journey from self-loathing to self-acceptance is one which likewise provides a template for the stages of self-actualization as well as a counterpoint to the mistaken notion that musicals are often defined by escapism, dishonesty, and shallowness.

Will you bring me to light?

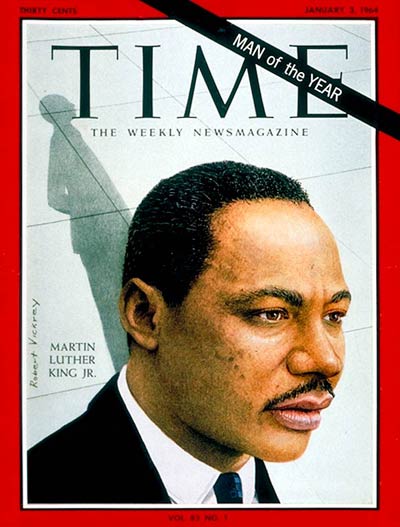

Further, like the character and her quest motif, Violet captures America at a pivotal crossroads in its collective history, when the polarizing forces of the Civil Rights Movement and the escalating Vietnam War were reshaping the nation’s perceptions and beliefs. With the prevalence of 50th anniversary commemorations of many seminal events of these moments, Violet offers that much more potential for the piece to speak to contemporary audiences. Just as it had half a century ago, our nation seems once again mired in a host of unprecedented, divisive conflicts and this backdrop of a previous time of staggering crises suggests that, now as then, we might reenter the light, rectify injuries, and endure.

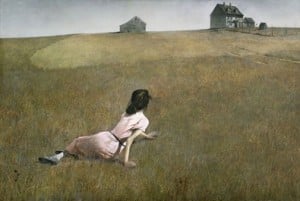

Hollywood images provide the impossible Technicolor ideals of perfection while the paintings of Andrew Wyeth capture the palette of stark beauty and longing in Violet’s world.

Among its concerns, then, are Violet’s challenges to blind faith in hobbled institutions. Each focal character undergoes a seminal reorientation and the power of the work as a whole is how seamlessly this wider world funnels through the show’s interpersonal relationships. Violet never preaches or offers facile solutions to the thorny issues it raises, but seeks answers instead through the emotional bonds it forges with audiences. That kind of pursuit of more valid truths is again what Musical Theatre does at its best, releasing us from partisan polemics into a purer communal identity.

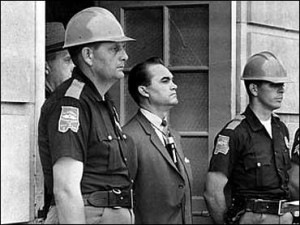

A Nation in Transit. Hope meets an Alabama Freedom Riders bus attack (1961), and the end of Camelot in November 1963, accelerating the ferment of the decade’s second half.

A Nation in Transit. Hope meets an Alabama Freedom Riders bus attack (1961), and the end of Camelot in November 1963, accelerating the ferment of the decade’s second half.

American in Motion: Political figures tracing the nation’s course of peaceful progress and stubborn conflict, and a new symbol of American mobility in the celebrated Mustang convertible.

The music you make counts for everything.

Another among the distinguishing features of this show, Violet’s personal pilgrimage is also a musical tour through the indigenous forms of American music. The American South contains the rich arteries of what is often referred to as the triumvirate of national styles: New Orleans jazz, Memphis blues, and Nashville country and western—each a definitive pulse in the lifeblood of American song, and all of which combine and are amplified in the sonic topography of rock ‘n’ roll. Violet’s compositions deliberately and memorably trace both this travelogue and lineage, too, finding where these forms of expression aspire toward and give voice to the spiritual, as well.

Amid the Airwaves: Changing iconography and shifting landscapes find echoes in the morphing sounds of the American South.

Amid the Airwaves: Changing iconography and shifting landscapes find echoes in the morphing sounds of the American South.

Give me just a minute though/ To ransack my portfolio.

As even this sweeping a sampling of Violet’s physical, cultural, and musical terrains makes clear, this current project is another bold, ambitious choice for the Summer Youth Conservatory. With a roster of successes behind it, ranging from evergreen classics like The Music Man and Guys & Dolls, to Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Oliver!, from more experimental works like Urinetown and The Mystery of Edwin Drood, to contrasting contemporary essentials Sweeney Todd and Hairspray, the program continues its original mission of offering the same kind of rigorous, adventurous, and illuminating experiences to its participants and audiences as those characterizing our university and professional stages. With its rare mix of panoramic drive, intimacy, and charged currents of feeling, the several levels converging in Violet shape an occasion to be embraced and, in making its story our own, embodied. As with Violet’s own fortunes, the journey can at points appear daunting, but in either instance the destination is well worth the trip.

Come along with Violet, July 20-31.

Click here to buy tickets.