By Lexi Silva, Dramaturgy Fellow

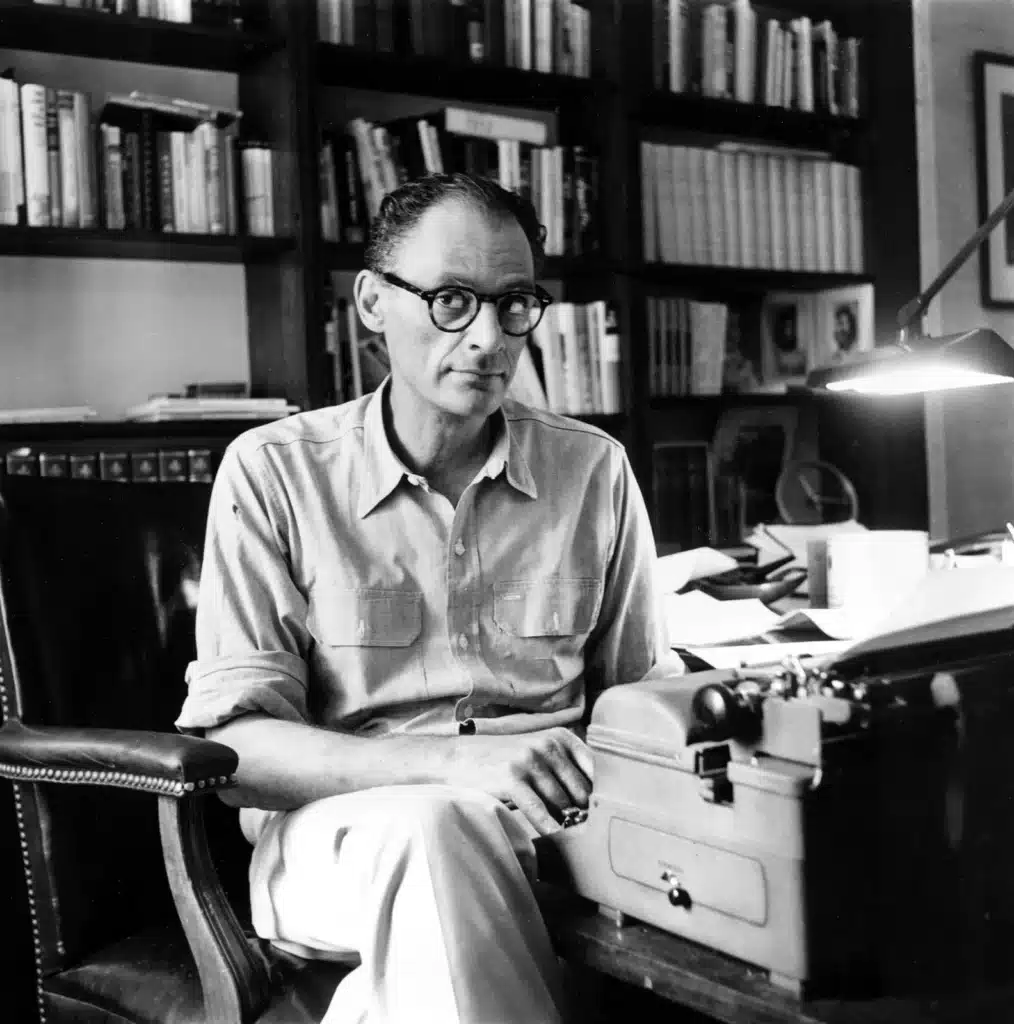

Welcome back to PlayMakers! Our season interrogating the American Dream continues with Arthur Miller’s magnum opus, Death of a Salesman. Whether the start of 2025 ushers in a spirit of auspiciousness or anxiety, a new year puts us all on the precipice of urgent possibility.

In early rehearsals for Salesman, I have been considering the nature of possibility as it relates to Miller’s philosophy on tragedy. In his essay, “Tragedy of the Common Man,” Miller contends: “I believe that the common man is as apt a subject for tragedy in its highest sense as kings were.” (“Tragedy” 3).

On the first day of rehearsal, Michael Wilson, director, stated that “[Salesman] is a story about real people” to whom, in the haunting words of Linda Loman, “attention must be paid.” (Salesman 46). These statements attempt to dismantle the suggestion that there is a hierarchy of suffering based on perceived importance.

The plight of the common man, as represented by Willy Loman, communicates a message that resonates with everyday people: tragedy does not mean passivity, and in Salesman, it is contingent on the presence of agency. Willy’s dreams are not bad dreams: to be heard, acknowledged, and understood are reasonable aspirations.

His maladaptive habits and inability to cope with change, however, prevent him from reaching these attainable goals. Genuine human connection with his sons and his wife is impeded by these shortcomings. If Willy could find community, he might find the sense of security he desperately seeks from external sources.

Despite Miller’s expert use of dramatic irony that maintains a steady tension throughout the play for audiences, tragedy strikes most effectively in the moments of hope that precede the inevitable. It is the possibility that the Loman men might overcome generational cycles that drives the play and ultimately facilitates heartbreak. The play can only end when Willy relieves himself of agency, denies himself of possibility, and can no longer carry on.

In this production, director Michael Wilson expressed interest in representing the tangible magic of bygone days to emphasize the expanse of Willy’s psychological experience. This is largely represented in the set designed by Jan Chambers in which the ephemerality of memory collides with a harsher material world. The set is all black and creates a suggestion of the Loman home, featuring a cellar overflowing with memorabilia of the past.

This physical space represents Willy’s mind, a reimagining that referenced Miller’s original impulse to have the play take place on a set that is a literal representation of Willy’s head. Through these visual representations, Miller’s poetic realism comes to life in the Paul Green theatre. The competing concepts of aspiration and desperation; dreams and reality are a direct confrontation of the ethos of the American Dream and an interrogation of its validity.

As much as Salesman explores the relationship between possibility and tragedy, on the other side of catharsis I find myself interested in the possibilities set before me this year. As audience members, we have the benefit of seeing the tragedy of Willy Loman’s life unfold before he does. In our own lives, we are not often afforded such accurate foresight. What we do have, however, is agency beyond the two-act structure.

The tragedy of Willy Loman’s life has been played out on stages across the world, and it always ends the same way: Willy doesn’t learn from his mistakes, but maybe we can. With Salesman in mind, I hope we can all make ourselves a little more available to the urgent possibility of building community amid isolation and hardship this year. Maybe that’s part of an America we can keep dreaming about together.

Death of a Salesman by Arthur Miller is on stage January 29 – February 16 at PlayMakers Repertory Company. See our show page to learn more and book your tickets!