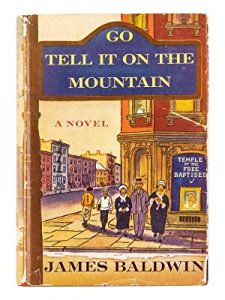

James Arthur Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924 in New York City’s Harlem and was raised under very trying circumstances. As is the case with many writers, Baldwin’s upbringing is reflected in his writings, especially in Go Tell It on the Mountain.

James Arthur Baldwin was born on August 2, 1924 in New York City’s Harlem and was raised under very trying circumstances. As is the case with many writers, Baldwin’s upbringing is reflected in his writings, especially in Go Tell It on the Mountain.

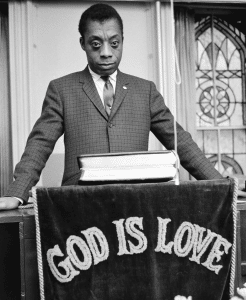

Baldwin’s stepfather, an evangelical preacher, struggled to support a large family and demanded the most rigorous religious behavior from his nine children. As a youth Baldwin read constantly and even tried writing. He was an excellent student who sought escape from his environment through literature, movies and theater. During the summer of his 14th birthday he underwent a dramatic religious conversion, partly in response to his nascent sexuality and partly as a further buffer against the ever-present temptations of drugs and crime. He served as a junior minister for three years at the Fireside Pentecostal Assembly, but gradually lost his desire to preach as he began to question Christian tenets.

Shortly after he graduated from high school in 1942, Baldwin was compelled to find work in order to help support his brothers and sisters; mental instability had incapacitated his stepfather. Baldwin took a job in the defense industry in Belle Meade, N.J., and there, not for the first time, he was confronted with racism, discrimination and the debilitating regulations of segregation. The experiences in New Jersey were closely followed by his stepfather’s death, after which Baldwin determined to make writing his sole profession.

Shortly after he graduated from high school in 1942, Baldwin was compelled to find work in order to help support his brothers and sisters; mental instability had incapacitated his stepfather. Baldwin took a job in the defense industry in Belle Meade, N.J., and there, not for the first time, he was confronted with racism, discrimination and the debilitating regulations of segregation. The experiences in New Jersey were closely followed by his stepfather’s death, after which Baldwin determined to make writing his sole profession.

Baldwin moved to Greenwich Village and began to write a novel, supporting himself by performing a variety of odd jobs. In 1944 he met author Richard Wright, who helped him to land the 1945 Eugene F. Saxton fellowship. Despite the financial freedom the fellowship provided, Baldwin was unable to complete his novel that year. He found the social tenor of the United States increasingly stifling even though such prestigious periodicals as the Nation, New Leader and Commentary began to accept his essays and short stories for publication. In 1948 he moved to Paris, using funds from a Rosenwald Foundation fellowship to pay his passage. Most critics feel that this journey abroad was fundamental to Baldwin’s development as an author.

“Once I found myself on the other side of the ocean,” Baldwin told the New York Times, “I could see where I came from very clearly, and I could see that I carried myself, which is my home, with me. You can never escape that. I am the grandson of a slave, and I am a writer. I must deal with both.”

Through some difficult financial and emotional periods, Baldwin undertook a process of self-realization that included both an acceptance of his heritage and an admittance of his bisexuality.

Baldwin’s move led to a burst of creativity that included Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, and other works. He also wrote a series of essays probing the psychic history of the United States along with his inner self. Many critics view Baldwin’s essays as his most significant contribution to American literature. They include Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen.

Baldwin’s move led to a burst of creativity that included Go Tell It on the Mountain, Giovanni’s Room, and other works. He also wrote a series of essays probing the psychic history of the United States along with his inner self. Many critics view Baldwin’s essays as his most significant contribution to American literature. They include Notes of a Native Son, Nobody Knows My Name, The Fire Next Time, No Name in the Street, and The Evidence of Things Not Seen.

In addition to his books and essays, Baldwin wrote plays that were produced on Broadway. Both The Amen Corner, a treatment of storefront pentecostal religion, and Blues for Mister Charlie, a drama based on the racially motivated murder of Emmett Till in 1955, had successful Broadway runs and numerous revivals.

Baldwin’s oratorical prowess—honed in the pulpit as a youth—brought him into great demand as a speaker during the civil rights era. Baldwin embraced his role as racial spokesman reluctantly and grew increasingly disillusioned as he felt his celebrity being exploited as entertainment. Baldwin did not feel that his speeches and essays were producing social change. The assassinations of three of his associates, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, shattered his remaining hopes for racial reconciliation across the U.S.

Baldwin’s oratorical prowess—honed in the pulpit as a youth—brought him into great demand as a speaker during the civil rights era. Baldwin embraced his role as racial spokesman reluctantly and grew increasingly disillusioned as he felt his celebrity being exploited as entertainment. Baldwin did not feel that his speeches and essays were producing social change. The assassinations of three of his associates, Medgar Evers, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, shattered his remaining hopes for racial reconciliation across the U.S.

At the time of his death from cancer late in 1987, Baldwin was still working on two projects—a play, The Welcome Table, and a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr. Although he lived primarily in France, he never relinquished his United States citizenship and preferred to think of himself as a “commuter” rather than as an expatriate.

The publication of his collected essays, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948–1985, and his subsequent death sparked reassessments of his career and legacy. “Mr. Baldwin has become a kind of prophet, a man who has been able to give a public issue all its deeper moral, historical and personal significance,” remarked Robert F. Sayre in Contemporary American Novelists. “Certainly one mark of his achievement… is that whatever deeper comprehension of the race issue Americans now possess has been in some way shaped by him. And this is to have shaped their comprehension of themselves as well.”

The publication of his collected essays, The Price of the Ticket: Collected Nonfiction 1948–1985, and his subsequent death sparked reassessments of his career and legacy. “Mr. Baldwin has become a kind of prophet, a man who has been able to give a public issue all its deeper moral, historical and personal significance,” remarked Robert F. Sayre in Contemporary American Novelists. “Certainly one mark of his achievement… is that whatever deeper comprehension of the race issue Americans now possess has been in some way shaped by him. And this is to have shaped their comprehension of themselves as well.”

A novelist and essayist of considerable renown, James Baldwin bore articulate witness to the unhappy consequences of American racial strife. Baldwin’s writing career began in the last years of legislated segregation; his fame as a social observer grew in tandem with the civil rights movement as he mirrored African American aspirations, disappointments and coping strategies in a hostile society. Baldwin died on December 1, 1987 in France.

Don’t miss the world premiere of “They Do Not Know Harlem” March 1-12, 2023, celebrating the spirit of James Baldwin in a multi-media dance theatre experience.

Written and edited by Jacqueline E. Lawton and Chyna Wiles.