by Gregory Kable, Dramaturg

Authority’s overturned. The age is sick, and desperate remedies alone will serve.

– C.G. Bond, Sweeney Todd: The Demon Barber of Fleet Street, A Melodrama (1973)

To paraphrase Voltaire, if Sweeney Todd didn’t exist, it would be necessary to invent him. A figure equally haunting the shadows of his Fleet Street storefront and the whole of the 19th century English imagination, the fiendish barber holds a telling place in the grinding progress of the Industrial Revolution and its headlong rush toward the modern world. The story of Todd and his conspirator Mrs. Margery Lovett offers a window into the wealth of conflicts—historical, social, political, and aesthetic—which characterize the age.

Whether truth, embellished fact, or the purest fiction, Sweeney Todd skyrocketed to legendary status in Britain alongside his first formal literary appearance in 1846. That narrative was serialized as a ‘romance’ entitled The String of Pearls in The People’s Periodical and Family Library, a deceptively staid name for a newspaper that would feature such an increasingly gruesome tale (likewise made palatable by its innocuous title). In a competitive market, The People’s Periodical, like many papers of its day, helped boost its readership with fiction offered in weekly installments at a bedrock price. In this, journalism was tapping into the expansive appetite for exciting and accessible literary entertainments, facing fierce rivalry in the burgeoning publishing world of ‘penny dreadfuls’ and ‘shilling shockers’ a populist genre through which enterprising publishers and prolific authors could thrive by pleasing a public in times where mass literacy was a growing trend but decades away from being compulsory. These works of suspense, swift reversals, and vivid action found a rapt public eager for their tension and momentum, and were natural fits for the form of Melodrama which dominated the century’s theatre.

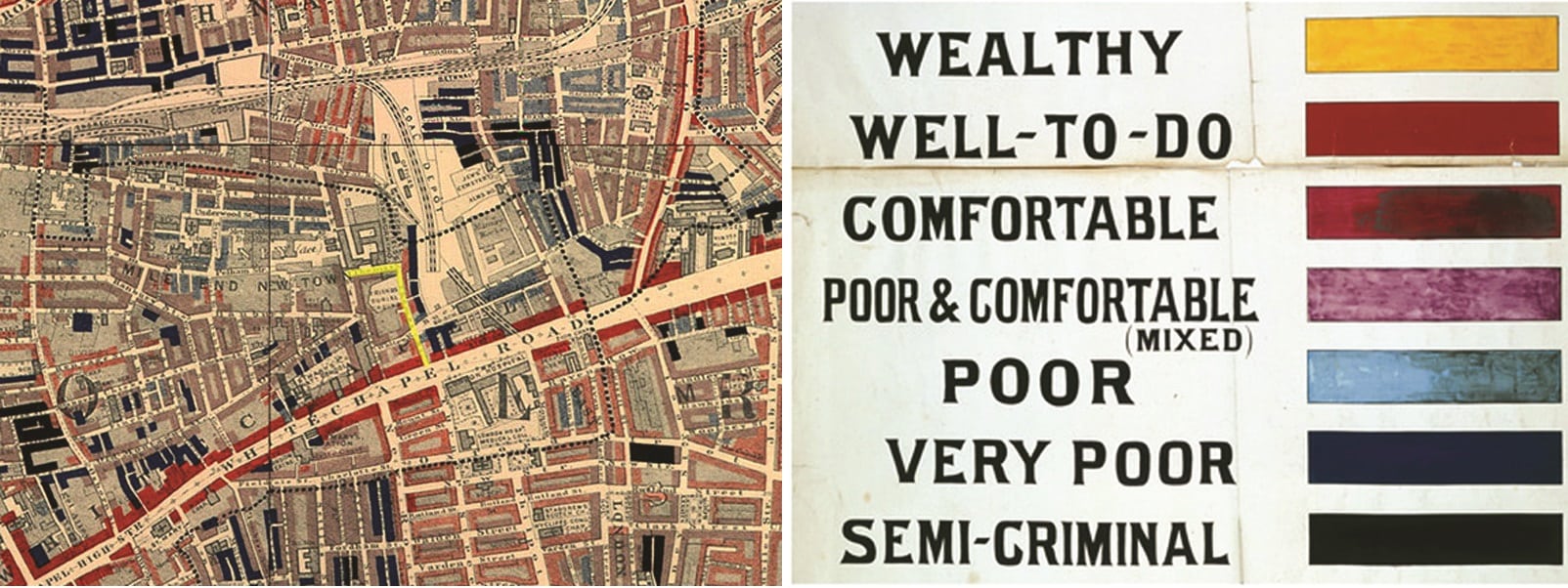

A Poverty Map from social chronicler Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People (1889-91).

A Poverty Map from social chronicler Charles Booth’s Labour and Life of the People (1889-91).

Sweeney’s story proved so compelling that within four years an expanded bound edition would balloon to five times the length of the serial; by 1880, that ratio would peak at eight times the original length. The taste for Sweeney had reached such a fever pitch that the first stage version of the tale appeared before the initial serialization had completed its run. The String of Pearls was adapted by George Dibdin Pitt and would be revived, revised, plagiarized and outright pirated with regularity throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Further print versions would debut in turn, each devouring those preceding it, and British cinema would soon follow suit by appropriating the piece for its medium as early as 1926, though it is a film version of a decade later, starring the fittingly named Tod Slaughter in the title role, that would become the favored standard.

Sweeney’s presumed address of 186 Fleet Street is the inverse of that other famous London landmark of 221B Baker Street. If the latter was the imagined fashionable site of Sherlock Holmes, literature’s most rational detective, Todd’s locale occupied the heart of the city’s more reckless impulses and sharp contradictions. Sweeney’s unadorned barbering service stood in the shadow of a long-established site of worship, the sacred literally abutting the profane, and Lovett’s nearby pie shop, connected through a maze of catacombs beneath the church, was itself in close proximity to the Inns of Court: divine and human law sharing space with the lawlessness of serial crime. Printers congregated in the neighborhood, too, drawn by the legal clientele of the area. Sweeney Todd, then, rises like the monsters of classic horror, a primitive asocial agent of chaos, whose emergence in the memorable phrase of film scholar Robin Wood signals “the return of the repressed”.

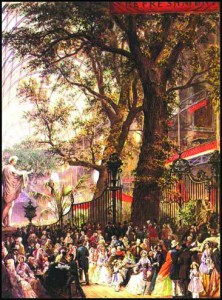

Industrialism feted at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, and its magnificent Crystal Palace vs. the struggle for survival of those in industry’s shadow.

Industrialism feted at London’s Great Exhibition of 1851, and its magnificent Crystal Palace vs. the struggle for survival of those in industry’s shadow.

If one side of Victorianism was the plight of the poor, the indigent, the mentally ill, and the economically displaced, Sweeney’s spree is that of an avenging angel, passing sweeping judgement on the widespread complicity he recognizes as perpetuating untenable conditions, and his macabre methodology exposes the vulnerability of all social compacts. The legend’s associations between cannibalism and capitalism are readily apparent, while in violating the bonds between provider and customer, social confidence itself is victimized. On the psychological level, the seemingly ordinary action of a shave turning lethal taps into those same primal fears that make the shower scene in Hitchcock’s Psycho, a pause in a graveyard in Night of the Living Dead, and the deadly outcome of a moonlit dip in the ocean in Jaws definitive moments in movie history. The Victorians delighted in the same flirtations with death and apocalypse that fuel many a contemporary entertainment franchise. From Jack the Ripper to today’s Jigsaw, this tumbling together of myth and reality, and descent into the dark side of human nature and experience have their own seductive fascination.

To the immediate right of St. Dunstan’s Church, the site of the shop and its infernal secrets.

Like the medieval contests between Carnival and Lent, 19th century popular literature and theatre continued the previous century’s competition between the sentimental and the gothic. On both page and stage, works sought to awaken empathy and the tender passions or traded in shock and awe instead. This ongoing conflict of sensibility and sensation found a perfect home in Melodrama, a form which embraces both tendencies at once. The clear-cut morality and representative figures of virtue and vice defining the genre upheld those pious values of duty, decorum, propriety, and dignity idealized by the age, making assaults on such norms deeply pleasurable through the foregone conclusion of their restoration by the final curtain. Across all media, then, the traditional narrative of Sweeney Todd was that of a cautionary tale.

This alters in 1973, when British dramatist Christopher Bond reconceived Sweeney once again, uniquely adding a tragic backstory to motivate Todd’s murderous passions, he reanimated something essential that had been slowly bled out of the story over its long history; the singular appeals of Melodrama were reunited with the starker power of Tragedy, and the capacity to recover that state of innocence which gripped its original audiences could at last put to rest the sense of indulgence and self-parody which had coiled around each subsequent iteration. Happening upon Bond’s version during its successful run in London, Stephen Sondheim recognized its potential immediately.

Next: Part 2, Sondheim & Sweeney

Sweeney Todd takes the stage beginning March 30th.

Click here or call our Box Office at 919.962.7529 for tickets.