by Jules Odendahl-James, Production Dramaturg

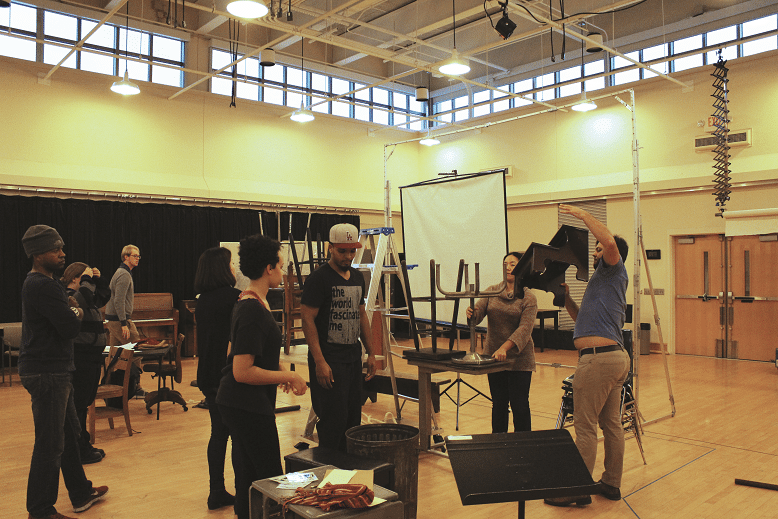

Cast and creative team for We Are Proud to Present… in rehearsal.

Cast and creative team for We Are Proud to Present… in rehearsal.

ACTOR 6: When you’re trying to make something.

Not everyone’s going to be happy during every minute of it

—We Are Proud to Present…

Devised theatre is a new term for when a collective of artists builds a show collaboratively functioning as writers, directors, designers, actors and crew. Such building borrows from a host of historical and aesthetic models: avant-garde and experimental art, physical theatre, documentary theatre, agit-prop theatre, dance theatre, digital/new media, art installation, performance art to name a few. Early examples of devising-esque practices in the mid-twentieth century American theatre can be found in ensembles like The Living Theatre, The Open Theatre, La Mama, San Francisco Mime Troupe and El Teatro Campesino who explored communal creation in works that broke with traditional dramatic form and actively engaged political and performance theory and practice. Around this same time, a broader understanding of performance as a set of participatory practices that can happen outside a formal theatrical setting was being explored for the purposes of public education, international development and political activism. Applied theatre, Theater for Social Change, Theater of Development, Community-based Theatre are different strains of this approach to performance in non-traditional settings with marginalized or underserved communities and non-actors that continues to this day thanks to the work of international artists like Augusto Boal, Peter Brook, Armand Gatti, American artists/scholars such as Michael Rohd and Jan Cohen-Cruz, and even closer to home, the North Carolina based company Hidden Voices.

Beyond the lack of a single playwright’s hand behind the performance script, devised ensembles share other qualities. They rely heavily on improvisation and physical exploration to develop dialogue, character and performance vocabulary. Settings can be minimal, composed of found objects in stripped down theatre spaces or more immersive, performed in locations where the divide between audience and artistic company is absent or constantly shifting. Devisers also research and reference a host of mediums (music, dance, visual art, film and television) and disciplines (philosophy, history, cultural and literary theory). They also work with personal narratives from either company members or found sources. The resulting compositions might be organized around a central theme and companies often engage meta-theatricality, performances that comment upon the very act of performance. They often break the fourth wall and speak to, even challenge the watching audience sometimes inviting them to interact with their performance in ways that change the show every night before our very eyes. Since the late 1990s, a new wave of American devising ensembles who engage a range of these practices have come to prominence. They include The TEAM, Ghost Road Company, SITI Company and Pig Iron Theatre Company, who recently joined with UArts in Philadelphia to construct the first MFA degree in Devised Performance.

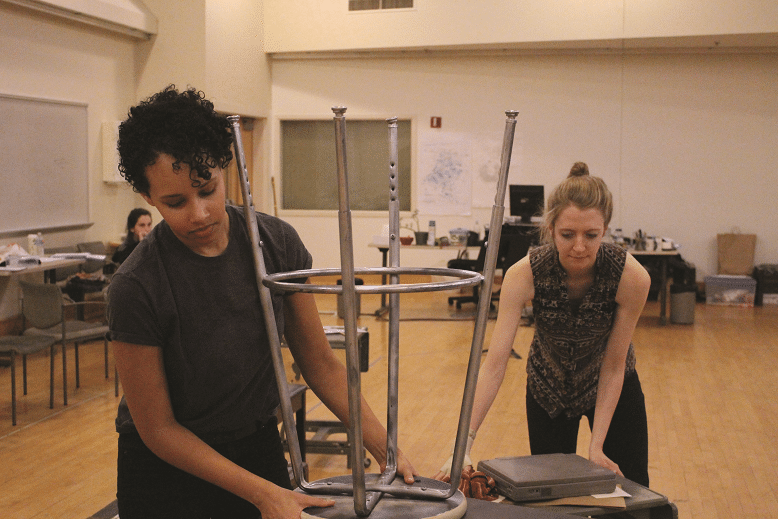

Caroline Strange and Carey Cox in rehearsal.

Caroline Strange and Carey Cox in rehearsal.

Perhaps now is the time to acknowledge that We Are Proud to Present… is not a piece of devised theatre. Even as its characters talk about their work as a “process” and a “presentation” and we see them engaged in collective composition of the performance, what you are watching has been scripted and organized by a single author. That said, it is not a play in which you will learn the complex history of the Herero of Namibia or their colonization and attempted extermination by Germany. In the words of the playwright, for “someone who is very interested in finding out something about the Herero, […] this is an incredibly disappointing play.” What Drury does depict are the ways in which this troupe of American actors must draw upon their own understandings of racial violence (perpetrated and experienced) in order to conceptualize the racial violence of another time, place, and culture.

ACTOR 1: None of us has ever been to Africa.

ACTOR 2: Yeah, and I don’t need to go to Africa to know what it’s like to be black.

ACTOR 1: You’re not supposed to be black, you’re supposed to be African.

ACTOR 2: There’s no difference between being black and being African. Africa is black.

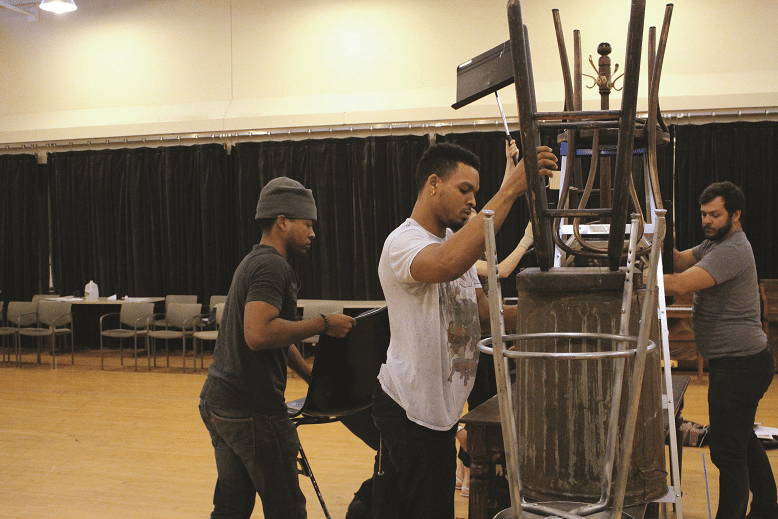

Genesis Oliver, Myles Bullock and Nathaniel Kent in rehearsal.

Genesis Oliver, Myles Bullock and Nathaniel Kent in rehearsal.

The Herero’s history allows Drury to investigate the productive discomfort of meta-theatricality. In this theatre there is no curtain; we have no choice but to watch the ways in which the company’s rehearsal and performance process morphs, breaks down, even explodes as their work requires their self-examination of America’s racial histories and the prejudices and privileges born out those histories. In order to illustrate how difficult it is to talk openly and honestly about race, power and representation in America, Drury engages four layers of performance at once: 1) her script, 2) the company of artists who rehearse and perform that script, 3) the company of artists within the script that slowly dissolves under the weight of its subjects — the genocide of the Herero by Germany and the legacy of slavery in the United States, and 4) you, the viewing audience. The open-ended process of devising allows Drury to dramatize the thorny process of saying and doing uncomfortable even unconscionable things.

Actors 1-6 are our daring proxies. German Südwestafrika is the backdrop against which this company plays out acts of racial violence that increase in scale and scope. They are young, inexperienced and naïve. Their collaborative process requires that unvoiced even unexamined assumptions be spoken and revealed. Once uncovered, however, these ideas and opinions merge with those of their source material in dangerous ways. Such is Drury’s endgame: to inspire us to take a good long look in the mirror and challenge our credibility to educate anyone on discrimination, equity and post-racial harmony while ignoring still unfolding American legacies of slavery, manifest destiny and exceptionalism.

ACTOR 3: You can’t take no walk in somebody else’s shoes and know

Anything.

You ain’t bought those shoes,

you ain’t laced those shoes up,

you ain’t put those shoes on day after day

you ain’t broken those shoes in.

Now you can borrow somebody else’s shoes, and you can walk as long as you want,

they ain’t your shoes.

In this way, We Are Proud to Present… seems particularly relevant to our here (the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill) and now (a national election year). Universities have become flashpoints for a larger national debates over the direction of the country, who can/should be included in its citizenry, and the evolution of its foundational values. On campuses across America, students of color are building coalitions and putting the tools of critique and performance to use in public challenge to university educators and administrators. These young activists are questioning institutional histories and patrons, demanding that structural impediments to equity, inclusion, and accessibility be dismantled. Along the way, like Actors 1-6, they encounter the limits of their knowledge, the difficult work of collaboration and compromise, and the physical, emotional price of confrontation.

The thing that I love about trying to write plays is that in theater you […] can have a matrix of questions. Most plays that I like don’t really answer any of them. You’re able to bandy ideas about without offering a resolution or a conclusion. It’s an exciting way to engage really big questions, I think, if you don’t have the pressure of concluding ‘Well, empathy … is a good thing. Or a bad thing.’

–Jackie Sibblies Drury, interview with The Appendix, April 2013.

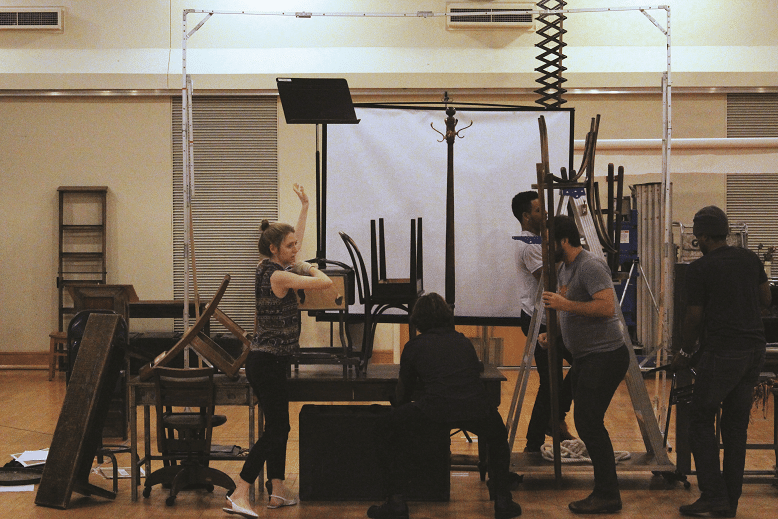

Cast of We Are Proud to Present… in rehearsal

Cast of We Are Proud to Present… in rehearsal

Just as this is not a piece of devised theatre, it is not a play that offers resolution. Action concludes but where we find ourselves at the end – from cast, to company of characters, to community of audience – will be widely variable. Dismissed by some, uncomfortable for many, and devastating for others. The theatre’s daring invitation to participate, even vicariously, in another’s terror and degradation has been debated by philosophers and politicians since the dawn of Western drama. Without a commonly shared catharsis, to what fate does Drury release us back into the world? But perhaps that is the point. We do not enter the theatre on equal footing, with a universally shared understanding or experience of reality. It would be a false promise, a negation of the hard fought, uncomfortable exchanges of the on-stage company to conclude with a kumbaya moment. To earn the empathy essential for the hard work of transforming society, we must be honest with just how little Americans know about each other and how much privilege must be sacrificed and wrongs must be forgiven before we can even think about taking our first steps together into an equitable future.

We’ll have more background to share in the coming weeks. In the meantime, don’t wait to get your tickets for this powerful production of We Are Proud to Present….

Click here for tickets or call our Box Office at 919.962.7529.